[

{

"name": "500x250 Ad",

"insertPoint": "5",

"component": "15667920",

"parentWrapperClass": "",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

Rochester has lost a beloved fixture of its cafe culture. You may not have ever spoken with him, but if you've visited Gibbs Street in the last several years, it's likely that you've caught a glimpse of accordion player Andy Hammond, who for years imbued the scene with a Parisian atmosphere. The so-called "Gibbs Street Gandalf" was a transient artist by choice, and though he depended on the good hearts of those who helped him out, he offered a deep and steady friendship in return to people from all ages and all walks.

Hammond found out he had terminal cancer in September. He was given weeks to live, but made it until February 6, when he died of glycemic shock. "He pulled through for so long," says Brian Boice, a Java's regular and friend of Hammond. "He didn't have a long expectancy at first, but he pulled through and everyone hoped he would make it through the cancer. If he hadn't gone into glycemic shock, I'm not sure he would be dead right now."

City Newspaper spoke with some folks who spent time with Hammond, and who provided anecdotes about what they learned of his life, and memories of time spent with him. You can add your own memories of Andy Hammond to the comments section below.

Mike Calabrese, owner of Java's Cafe, has known Hammond for around 10 years, which is about as long as he'd been hanging out at Java's. "I got to know him when he just showed up and he was playing the accordion," Calabrese says. Hammond would play in the alley around the side of the cafe every morning, but Calabrese invited him to pull up a chair out front, feeling that Hammond contributed beautifully to the scene.

"He would play literally every morning for years," he says. "In the winter, in the cold months, sometimes he'd play inside around lunch time. He was just part of the cafe. Everybody liked him. I think he taught himself the accordion, he had that kind of self-taught, rough, beautiful energy about him when he played. So many people said the same thing -- he made the street feel like Paris. He'd be singing and playing."

One day Hammond asked if Calabrese would mind if he brought the stuffed coyote from inside the cafe onto the street with him. "For a period of probably three months, he'd go inside, get a chair, pick up the coyote, and put it next to him while he was playing, and I always loved that," he says. There are more photos of him with that coyote in front of him..."

Calabrese says Java's will keep a photo of Hammond up in the cafe, and that the Java's family has been invited to the spreading of Hammond's ashes, which will take place this summer on family property in the Adirondack mountains.

A Syracuse transplant from Rochester, Matt Zhelezniak, was a Java's regular and knew Hammond for

about four years. They became close friends, and Zhelezniak

was invited on several occasions to spend time with Hammond in the Adirondacks.

"He felt like Hoel Pond was his real home,"

he says. "Seeing him in his element, his favorite place, was really

great." Usually four or five people attended these mid- to late-August

gatherings, canoeing and relaxing with good music and good food.

Hammond "was extremely knowledgable on many different topics, and a great conversationalist," Zhelezniak says. "He was an expert musician, with a real heart of gold. Knowing him was an honor. I really loved him as a person and I'm gonna miss him very much as a friend."

Carlie Fishgold, long-time Java's barista and a student, met Hammond three or four years ago. "I remember the first time I ever saw Andy, he was playing a really, really low, version of a Beatles song -- "For the Benefit of Mr. Kite" -- and it just bowled me over; it was the most beautiful version of a Beatles song I've ever heard," she says. "And then I kept looking for him everywhere, at Javas and at the market. I'd bring him a coffee and have a couple of words with him."

Fishgold says she loved to hear Hammond's stories about the past.

"He loved theatre and was an actor most of his life," she says. "He used to spend time in Cape Cod, every summer for four years, with other actors from a New York theater company. They'd go and camp on an island. In Provincetown, he played his first game of Pong ever. It was late at night, they'd smoked a whole bunch of weed, and they walked into this little café-bar. He said it reminded him a lot of the Island of the Lost Boys in Peter Pan. And the police showed up. I just liked to listen to him tell stories like that, and hear where he came from. Not so much where he was going, because I think a lot of people tried to tell him what to do -- they were really concerned for him."

Fishgold says that Hammond had three or four accordions, which he sometimes hid around the cafe. "Under the piano, in the creamer station, or parts of the tea room where no one would really notice," she says. "Nobody really seemed to touch them -- he used the cafe as a sort of a waystation. When he'd go out to the Adirondacks and come back, he'd sometimes use Java's sort of like a little bus station. Check his email and everything."

Java's regular Dennis Pollard and Hammond were coffee-drinking partners for the past few years, but their conversation was more on a casual, daily basis than focused on the past. "I know he graduated from Brighton High School in 1974. He lived in New York City for a while, and participated in Broadway revivals or off-Broadway stuff," he says. "Andy had a huge knowledge of Broadway songs, and was in 'South Pacific.' He showed me a picture of himself in the cast, he was really proud of that."

Pollard says that Hammond was an outgoing guy, and never had negative things to say about anybody. "I never heard him say a single rude thing," he says. "And I think that's important, you know?"

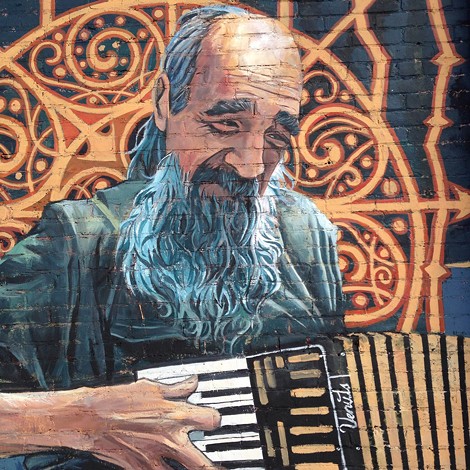

Artist and musician Caitlin Yarksy says she aware of Hammond from visits to Gibbs Street, but didn't know him personally until she asked for him to pose for her Wall\Therapy mural last summer.

"There was an emphasis on portraiture and Rochester figures, and instead of going with somebody famous, I wanted to go with somebody local, who was a fixture in Rochester culture," she says. "Andy had a great face, and he was really loved in this town, so I thought he'd be a good pick."

Yarsky found out shortly after they worked together that Hammond was terminal, and she says when she called him, they discussed the irony of the name of the mural: "Andy and the Big Dead Waltz." The title was drawn from an album her singer-songwriter father put out when she was growing up.

"I felt really strange about it," she says. Hammond told her it made him chuckle.

"He had a good, dark sense of humor, and I'm glad it didn't freak him out or offend him or anything," Yarsky says. "He seemed like a really gentle and kind person, and I wish I knew him better."

Fishgold says that after Hammond found out he was terminal, he got a ride out to his family's cottage at Hoel Pond and spent a couple of weeks there, "Kind of like his dying wish. He told me that it was perfect, because he got the perfect amount of alone time, a little bit of time with some friends who came up to visit, who brought him food and books and things, and a little bit of time with the neighbors who were around when his parents were around, so it was kind of like the family time he needed, as well," she says.

"It's really easy to be judgmental of people who choose a lifestyle that requires a little more of society, but I think he really gave a lot to people in passing just by playing music everyday," Fishgold says. "He became part of Rochester's cultural fabric, and there's no one who will ever fill that space again."

Speaking of...

-

Community remembers Christopher Morrison

Jan 15, 2019 -

Feedback 3/4

Mar 4, 2015 -

Frank reviews perCepTION

Sep 19, 2014 - More »

Latest in Culture

More by Rebecca Rafferty

-

Beyond folklore

Apr 4, 2024 -

Partnership perks: Public Provisions @ Flour City Bread

Feb 24, 2024 -

Raison d’Art

Feb 19, 2024 - More »