[

{

"name": "500x250 Ad",

"insertPoint": "5",

"component": "15667920",

"parentWrapperClass": "",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

The large, main room of Workinman buzzes with people — many in their 20's and 30's — sitting at long tables filled with computers. Some have headphones on and are steadily plugging away at the projects on their screens, while others talk across the open room or walk over to another one of the multi-person desks. There's a relaxed, modern atmosphere to the space — it doesn't hurt that there's also a well-used yoga room and a conference room that looks more like a video gamer's lounge with a large TV, Nintendo Wii, and shelves of games next to a large dry erase board scribbled with drawings and notes.

It's how you would expect a forward-thinking video game development studio to look. Really, Workinman classifies itself as an "entertainment based content creation company," but its specialty has become creating video games for the youth market — with regular high-profile clients like Disney, Nickelodeon, Shockwave, and more recently, Nintendo and Sesame Street.

Jason Arena, Workinman's founder and chief executive officer, moved his company from Pittsford into this location on North Goodman Street earlier this year, partly to be closer to the heart of Rochester, but also to accommodate his growing company. Workinman employs 42 people, Arena says, from designers, illustrators, and animators to developers, and has worked on more than 350 titles — around 100 last year alone.

Workinman has seen a steady growth since Arena founded the company in his house in 2006 and he brought on his first employee, an RIT student who needed one more class to graduate.

"He would show up at my house every morning at 8 a.m., my wife would cook us breakfast, lunch, and dinner, and we would hang out and work until all hours," says Arena, who is also an associate professor in design at RIT. "That's the kind of company this grew from. Everybody was there and a big family. I think it is still a big family, maybe just not as small and intimate as it used to be."

A burgeoning video game development community in Rochester has started to take hold in recent years. Along with Workinman's rapid growth, a handful of companies — including Darkwind Media, BrokenMyth Studios, Second Avenue Learning, and Ambrosia Software — have established themselves in the area and are starting to see the formation of a viable industry.

There's also diversity among the companies. Workinman specializes in making games directed toward younger gamers. Second Avenue Learning has made a name for itself by building educational games. Darkwind, which is working on its second original title, is heavy on programmers and has had success with contracting services for other developers. BrokenMyth Studios is a full-production studio that has worked with numerous companies — both gaming and non-gaming — on 3D visualizations. Ambrosia, which incorporated in 1993, creates software and games predominately for Macintosh.

"It's getting serious," says Stephen Jacobs, the associate director of the Media, Arts, Games, Interaction & Creativity Center (known as MAGIC) at RIT. "It has moved from, 'That's a really good start,' to 'Oh, isn't that cute,' to 'Wow, there it is.' Between the five companies, there's maybe 100 to 120 people working. That's really no joke."

Fast growth

Around the time Arena was studying at Buffalo State College to be an art teacher and questioning whether teaching was the right career path, a girlfriend said he should check out possibilities on the web. He was hooked and started learning HTML on his own.

"I've been doing this stuff since 1994," Arena says, "and I started when the technology for delivering interactive content — like the cool stuff, not just websites — was Director and then went into Flash; then Flash went to HTML 5. I've seen these shifts, and every time, I'm OK with it. I'm like, let's do this; that's what makes this job exciting for me."

Arena began making websites and interactive content and went on to work for Nickelodeon in 1997 during graduate school. After he left Nickelodeon in 2001, he moved back to Rochester to be closer to family and began doing freelance work on interactive and marketing projects. He formally founded Workinman in 2006, and around 2007 the company began to transition into just making games.

"It was just something that we were really good at, and we focused on that," he says. "We used to do a lot of marketing websites and interactive experiences using Flash technology, but we might do a marketing site for a movie or TV show. We got out of that and started focusing primarily on games and the youth market."

"I think that's where our talents lay," Keith McCullough adds. McCullough, the company's chief technology officer, joined Workinman in 2007. "I knew how to make games and liked making games, so that just made more sense than working on something we weren't naturals at."

The majority of Workinman's games are played in web browsers or are available as mobile apps, and they feature instantly recognizable kids' characters like SpongeBob SquarePants, Kung Fu Panda, Power Rangers, and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. For Workinman, small mini-games might take about eight weeks to complete with a two-person team, while projects on iOS and Android could take eight months to a year with a six- to eight-person team. Arena says the company usually has eight to 12 games in the works at any given time.

On top of that, Workinman is currently developing "Deathstate," a more adult game created by local artists Matt Leffler and Peter Lazarski – a description at deathstategame.com says it is "Fueled by their obsession of Cave bullet hell shmups, Hellraiser films, Lovecraftian horror, and dungeon Crawl" — that they hope will launch in Steam for PC and Mac, McCullough says.

Arena didn't set out to create a good-sized gaming development company, he says, and the growth has been organic.

"It all kind of worked out," he says. "I moved back here because I wanted to be in Rochester, close to my family." Arena thought he would be a freelancer, but as more people started asking for work, he leveraged Rochester's resources, namely the Rochester Institute of Technology and its students, to build his company.

Of Workinman's 42 employees, 39 of them are graduates of RIT.

"Trying to figure out why there's a small hub in Rochester, you really can't overlook RIT for a major resource," McCullough says.

The common thread

In Rochester's emerging video game development community, RIT is an undeniable key factor. The university's School of Interactive Games and the Media, Arts, Games, Interaction & Creativity Center have played a vital role in producing a knowledgeable development workforce and entrepreneurs looking to create their own small gaming studios.

"I think what you see now is that the output of students coming from RIT is incredibly high," says Colin Doody, president and creative director of Darkwind Media. "Of course some people are going to stay in this area and coagulate."

Of Darkwind's 15 employees, 14 are graduates of or co-op students from RIT, Doody says.

"There is a ton of talent," Stephen Jacobs says. "RIT is a co-op school, and RIT co-ops have driven company growth large and small in Rochester for over a hundred years. So it's no surprise, and interest in gaming as an industry is national."

The School of Interactive Games and Media offers a B.S. and an M.S. in game design and development, and a B.S. in new media interactive development. Students in these programs learn skills needed to artistically design video games (incorporating illustration and animation) and then develop the necessary content, technologies, and digital systems that form the framework of the game (through programming and coding).

When discussion about teaching a course in game programming began more than 10 years ago, says Jacobs, RIT's degree in information technology had five tracks, one of which was in interactive media. Andrew Phelps, now the director and founder of MAGIC Center, was a graduate student in the interactive media track but wanted to start teaching a game development course. In 2001, RIT had the nation's first graduate level game programming class, taught by Phelps. Still, it was several years before a full program was constructed, Jacobs says.

"Even though we were one of the first colleges to have this — it wasn't like today, where everyone is falling over themselves to start game degrees if they don't already have one — 10 years ago, you had to convince your board of trustees and the academic administration," Jacobs says.

But persistence paid off: the graduate program in game design and development was formed in 2006, and the undergraduate program started in 2007. In 2009, Phelps started the department of interactive games and media, which in 2011 became the School of Interactive Games and Media. The undergraduate game degree now takes in 180 students a year.

Even before 2006, RIT saw 15 to 30 people graduate with a master's degree in IT who had taken six classes in games, some of whom have already risen into high levels of game creation. This includes Anna Sweet, one of the Steam Machine project heads at Valve, the video game developer known for Half-Life and Portal.

In February 2013, RIT created The RIT Laboratory for MAGIC, a separate university-wide research center with roots in the degree. The center helps faculty, students, staff, and alumni with work on interdisciplinary projects. Work with the MAGIC center can be traditional university not-for-profit research while for-profit production projects are done within the center's MAGIC Spell Studios division.

"We kind of see ourselves in many ways offering a pre-incubator," Jacobs says.

During the more than a decade of teaching classes in game design and development, Jacobs says, the video game industry has gone from "locked down" to open. For a long time, as console gaming — like the popular PlayStation, Xbox, and Nintendo machines — moved forward, it became harder to be an independent or a small game developer. But in recent years, popularity of games on mobile devices and the launch of the App Store on Apple's iOS really flipped the notion of console dominance and made big companies pay attention to the indie market. As it became easier and cheaper for audiences to access new games, small game developers had more open doors to compete in the game market.

"That's also helped drive local market in general," Jacobs says. "And because all of that talent is here, it's not surprising, these companies live off our students."

Why stay?

Colin Doody, Brian Johnstone, Matthew Mikuszewski, and Scott Flynn co-founded Darkwind Media in 2007 while they were still RIT students who wanted to create a game company.

"We started talking to some people at the business school, and they basically had no idea what to do with us," Doody says. RIT put them into its Venture Creations incubator — located at 125 Tech Park Drive, adjacent to RIT's campus.

"We were pretty serious about doing a business," Johnstone says. The group wanted to build its own game engine — the software framework that allows for the creation of video games — but started getting clients asking for 3-D graphics. "That wasn't necessarily games, but was related to games using our engine and things like that."

Though game creation didn't take off immediately, Darkwind took a slow and steady approach, taking as much work from clients as they could get. While Doody and Mikuszewski worked on creating websites and graphics for clients, Johnstone and Flynn worked on the game engine.

"We thought we were on a road to become a fairly large tool company that was going to help other people make games or something like that," Johnstone said. "It's a notoriously difficult industry to break into if you're just a bunch of dudes with no reputation and just say, 'Hey, we're making games, pay attention to me.' We thought we had this interesting, sneaky way of getting around the side and getting in."

It worked. Taking new clients led to more work, which led to more opportunity for Darkwind — like working with graphics card maker Nvidia and then a major relationship with Unity Technologies, which created the popular Unity game engine and development platform. Eventually Darkwind was able to move to just taking jobs related to games, like porting (taking games from one platform and making them work on another) and first-party or second-party game development.

Johnstone says he isn't sure how many titles Darkwind has worked on, but estimates it was in the hundreds — though many of those were in a smaller, specialized capacity, like porting, or programming on a specific part of the game. Darkwind has had significant involvement with six or seven games, Doody adds, including Republique, The Harvest, and Skylanders Cloud Patrol. And the company designed and developed its first original game, Kona's Crate, in 2011.

Darkwind is now working on a new original game, Wulverblade, with the artist Michael Heald and his studio, Fully Illustrated. The game — which follows a warrior fighting against invading Romans in 120 A.D. Britannia — is an old-school arcade side-scroller for the Xbox One and Steam. Darkwind is looking at a 2015 release date. (You can learn more at wulverblade.com.)

After graduating RIT, the founders of Darkwind talked about moving away from Rochester, but as the company became busier, the guys began settling in.

The conversation went from "'Should we move?' to 'Why should we move?'" Johnstone says. "Then we started to think about: If we moved, what would we gain and what would we lose?"

If Darkwind moved to a game development hub — a city like San Francisco, Seattle, or even Boston — there would be an existing community of developers available. On the other hand, the company would lose the security of being in a smaller area like Rochester, and it couldn't benefit from a relationship with RIT.

"Our company is our employees," Johnstone says. "We're as good as the people who do the work. If we can extract the best people from RIT, then we're doing really well."

The Rochester community of developers itself is still new, and so not yet fully established, Johnstone says. But with more students graduating and able to find jobs in Rochester, that hub is beginning to form.

"There is a growing knowledge of us and therefore Rochester," Doody says. "I think as the studios grow, as more companies emerge, there will be more visibility and therefore more community among our companies. But everyone is still growing."

A piece of $21 billion

While the beginnings of a video game development industry are present in Rochester, there are steps that could be taken to help it continue to grow: the release of a well-known game, the recognition of a major studio, and of course, money.

"We have the talent," says Stephen Jacobs. "What we're missing, and this goes for any kind of industry, start-up business: we do not have the venture action you get in Boston, D.C., San Francisco, and New York City. Talk to any business reporter, and they will tell you that everyone is beating their head against the wall, because it takes money to make money, and getting the money to get off the ground is a huge struggle."

There are opportunities to obtain the funds needed to start a business, Jacobs adds, but the reality is that the pool in Rochester is much smaller than in other cities.

New York State is starting to take notice, though. In October 2013, the Senate Select Committee on Science, Technology, Incubation, and Entrepreneurship hosted a roundtable discussion with legislators and industry experts at RIT on how video game design and development could be promoted in Upstate New York.

"This is a huge and highly profitable industry, which has exceeded even Hollywood in total revenue for almost a decade," Senator Ted O'Brien noted in a press release at the time. O'Brien participated in the roundtable, which included Colin Doody and Jason Arena.

"With RIT having top-10 programs in game design both for undergraduate and graduate students, I am deeply interested in learning more about how we can help remove barriers and power-up Rochester and the Finger Lakes," O'Brien's press release said.

In 2013 alone, video gaming was a $21 billion business in the U.S. That same year, New York was fourth among the top five states for game industry employment. The roundtable discussed how to develop a better support network for young entrepreneurs and how to enhance the abilities of New York State universities to help young people commercialize their ideas.

"They're trying to figure stuff out," Jacobs says about the follow-up to the discussion. "Everybody wants this to happen. It's just literally easier said than done."

Still, Jacobs believes the local industry will continue to grow if the business is there.

"The potential is here, and we have been showing solid, incremental growth for a while now," he says. "It's very clear this is not a fluke or an accident."

Editor's note: RIT's Stephen Jacobs is a member of the board of directors of this newspaper. He did not participate in the initiation or execution of this article.

Latest in Culture

More by Jake Clapp

-

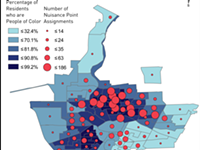

Report: Rochester nuisance law has racial impact

Aug 15, 2018 -

ROCK | Incubus

Aug 8, 2018 -

Album review: 'Honey from the Rock'

Aug 1, 2018 - More »