[

{

"name": "500x250 Ad",

"insertPoint": "5",

"component": "15667920",

"parentWrapperClass": "",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

It is a breezy, sunny spring day in the hamlet of Mumford on the western edge of Monroe County, and two women in well-worn dresses, dirty aprons, and white bonnets are at work in a farmhouse kitchen. An open door helps cool air circulate around a wood fire oven that’s belching heat into the tiny room. One woman periodically checks the temperature of a massive vat of milk that’s slowly heating, while the other looks on, learning the skill of making cheese.

Nearby, shelves hold older partial wheels of cheese, herb-infused vinegar, and various jars of fruit jams. Outside, seedlings have begun to sprout from the sun-warmed soil in the garden. Down the lane, a farming couple pick flowers on their way to tend to their cows and pigs. They pass a general store, a dressmaker’s shop, a brewery, churches, and a schoolhouse.

If their world sounds like something out of the past, that’s because it is. They’re in a recreation of an historic village at the Genesee Country Village & Museum, with its 68 authentic buildings on more than 600 acres of land, where visitors learn what everyday life was like for average people living in 19th-century rural New York.

What life was like for average white people, that is.

Black or Indigenous historic interpreters, as the denizens of this village are known, are scarce at the museum, which like many other institutions of its kind is grappling with how to better represent the experiences of native peoples and people of color who once lived here.

After decades of limited representation of people of color, and amid a nationwide reckoning on racial injustice, the museum has been engaging in some institutional soul-searching. Change, its officials pledge, is in the works.

“We recognize as a museum, particularly one that's focused on 19th-century history, that it's important for us to expand some of the stories that we're telling,” Kara Calder, the senior director of programs at the museum, said.

To that end, the museum is staging its inaugural celebration of Juneteenth on June 19 with programming that focuses on what Calder described as “what the lives of Black individuals and families were like at that time,” with Black historic interpreters telling those stories.

Juneteenth marks the anniversary of the summer day in 1865 when federal troops enforced the emancipation of a quarter of a million enslaved people in Galveston, Texas — more than two years after the Emancipation Proclamation ended slavery. Word of emancipation hadn’t reached — or was ignored by — slaveholders in more geographically isolated areas of the country, until Union Major General Gordon Granger and his army stepped in.

Plans for a Juneteenth event at the museum were actually in motion for 2020, Calder said, but were placed on hold because of the pandemic.

The museum has tapped Black historic interpreters in the past as consultants and collaborators for specific projects. Some of the interpreters pose as prominent historical figures for special events.

Last year, for instance, the museum incorporated into its Yuletide Celebration event a scene about Watch Night, a late-night Christian service held on New Year’s Eve that commemorates when African Americans gathered in churches on New Year's Eve in 1862, to await the hour when the Emancipation Proclamation would take effect on January 1, 1863.

But museum officials acknowledge that these instances aren’t consistent enough to accurately represent what life was like for average people of color in this region.

A ‘LIVING MUSEUM’

Since its founding in 1966, Genesee Country Village & Museum has functioned as a “living history” museum, dedicated to preserving tangible history through the buildings and artifacts transported to the grounds from all over western New York, and to showcasing what life was like through the work of historic interpreters who interact with the visiting public.

The site feels like an authentic village, and there are many bits of the collections that stand out. There is George Eastman’s childhood home, a stately little structure built in 1840 in the rural Oneida County village of Waterville. There are the wedding outfits of Frederick Douglass and his second wife, Helen Pitts, which are currently on display in the museum’s gallery with information on the variety of ways that enslaved and newly-free Black people’s marriages were or were not recognized.

“The most important thing I always tell people when I'm doing presentations is it's the nameless and faceless that we have to pay homage to,” said David Shakes, the director of the Rochester theater troupe The North Star Players, who is one of a few Black historic interpreters who has a longstanding relationship with the museum.

He has consulted with regional and national historic organizations for decades, and portrayed Frederick Douglass and abolitionist and playwright William Wells Brown at Genesee Country Village many times over the years.

“We know Frederick Douglass, we know Harriet Tubman,” Shakes said. “We know some of the icons, but I like to take a moment to say, ‘Hey, there are people who did things to help other people and help causes that we will never know and we need to recognize and take a moment for that.’”

Representation of Black and Indigenous people isn’t a small issue at Genesee Country Village, particularly considering the breadth of the museum’s educational responsibilities. The museum annually hosts educational programs for between 18,000 and 20,000 schoolchildren; 4,000 to 5,000 of whom attend Rochester public schools, where 53 percent of students are Black and 33 percent are Hispanic.

“Certainly in our school programs we have diversity,” said the museum’s chief executive officer, Becky Wehle, who is the granddaughter of the village’s founder, John L. Wehle. “But then as we do better and engage more community partners, we will hopefully continue to attract a broader audience as well. ‘This was what western New York in the 19th-century was like, there were all different kinds of people here’ — our mission is to tell that story. And so that's where this ties back to giving a fuller picture of what the community looked like and what the activities that were going on were.”

There are some obstacles to inclusion, however. Funding is one of them, Wehle explained. A lot of government grants don’t cover seasonal or part-time employees that make up most of the historic interpreter staff.

“Our interpretation staff, aside from a handful of supervisors, are not year round, because we're only open from full time from Mother's Day until October,” she said. “So that that's a big part of the challenge as well. We have been trying to identify some of these barriers, and figure out: is there a way we could create a position that is potentially funded from the outside, that would allow someone to work year-round?”

Another challenge is what the museum can afford to pay its interpreters. Senior Director of Interpretation Brian Nagel said it is tough to attract people who might make more money elsewhere to drive to the edge of the county line to do seasonal work for minimum wage.

“Before I arrived, the museum got an (Institute of Museum and Library Services) grant for doing an interpretive master plan,” said Nagel, who has been with the museum since 2005. “So we brought in experts from various areas to try to develop a plan for how we wanted to move forward over time. And so we've been working at that a little bit. But certainly getting into a more diverse interpretation has been a challenge. Fighting for STEM, other kinds of activities, has been easier than trying to break that diversity barrier.”

A NOD TO REALITY

Genesee Country Village’s buildings and interpreters represent a wide period of time in western New York. The museum has one foot in the era when slavery was active in New York state, and the other in the time after 1827, when it was abolished.

On either side of that year, though, there were thousands of formerly enslaved fugitives living free-but-furtive in New York. Even after abolishment, slave catchers would descend on northern cities and villages in pursuit of fugitives, often in cahoots with police and judges.

Mention of this reality is vague at Genesee Country Village. A visitor might learn about the Underground Railroad, or hear mention of the Abolition movement and the support it had in area towns. But on a typical day visitors will find no substantial focus on Black people’s reality during these times.

The museum’s Juneteenth celebration is a nod to that reality.

Such commemorations have been gaining support locally and nationally the past few years. In 2020, Juneteenth became a state holiday in New York, New Jersey, and Virginia, and there’s an ongoing push for Congress to recognize it as a federal holiday.

Honoring Juneteenth, which takes place Saturday, June 19, from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., will include storytelling, poetry, activities, and education — from the mouths of Black historic interpreters — about what life was like for Black people in western New York when emancipation was complete.

Visitors will hear stories of prominent African American figures, including Shakes’s portrayal of William Wells Brown, but also see representation of average Black people living in western New York during the time when news of emancipation went national.

“A number of former enslaved individuals seeking family members would have posted notices, either broadsides on boards or notices in papers,” Calder said, adding that this aspect will be represented both in printed broadsides posted at the museum’s print shop, and through live interpretation of families seeking newly freed family members.

That’s where Cheyney McKnight comes in.

McKnight is another historic interpreter tapped by Genesee Country Village to present at Juneteenth. She’ll work with a small group of other interpreters to tell a story of what it may have been like for a newly emancipated southern Black family to encounter a northern Black family, in a time period when folks were seeking sold-off family members long separated from them.

“We have a tendency to really focus on extraordinary circumstances,” McKnight said of the typical focus on famous historic African Americans.

“The reality of the 19th-century in America is that the average Black person was enslaved,” McKnight said. “But we have other realities. Upstate New York had Black people who were free since the American Revolution. And so I wonder, when those Black people met Black people who were running away to the north . . . what were those interactions like, what were the cultural differences they encountered?”

Based in New York City, McKnight is a living historian who operates under the company name Not Your Momma’s History, and, like Shakes, has been involved in historic interpretation for many institutions and groups both locally and on a national level.

In her travels and collaborations, McKnight says she’s taken note of some institutions that are doing inclusion and representation well.

“The Whitney Plantation in Louisiana is just doing it so well,” she said. “The way in which they approach interpreters who should be interpreting. I had never before been to a plantation where they were really straight-up. And I think it's very important to have descendants of the enslaved community present in the conversation.”

Representation is important not only to paint a more complete portrait of life in 19th-century western New York, but also as an opportunity for discovery, Shakes said.

He said he’s witnessed audience members connect with material he presents on the Underground Railroad, sometimes sharing their small towns’ involvement in the clandestine network of safe houses and routes.

“We're still learning things,” Shakes said.

Rebecca Rafferty is CITY's life editor and can be reached at [email protected].

Nearby, shelves hold older partial wheels of cheese, herb-infused vinegar, and various jars of fruit jams. Outside, seedlings have begun to sprout from the sun-warmed soil in the garden. Down the lane, a farming couple pick flowers on their way to tend to their cows and pigs. They pass a general store, a dressmaker’s shop, a brewery, churches, and a schoolhouse.

If their world sounds like something out of the past, that’s because it is. They’re in a recreation of an historic village at the Genesee Country Village & Museum, with its 68 authentic buildings on more than 600 acres of land, where visitors learn what everyday life was like for average people living in 19th-century rural New York.

What life was like for average white people, that is.

Black or Indigenous historic interpreters, as the denizens of this village are known, are scarce at the museum, which like many other institutions of its kind is grappling with how to better represent the experiences of native peoples and people of color who once lived here.

After decades of limited representation of people of color, and amid a nationwide reckoning on racial injustice, the museum has been engaging in some institutional soul-searching. Change, its officials pledge, is in the works.

“We recognize as a museum, particularly one that's focused on 19th-century history, that it's important for us to expand some of the stories that we're telling,” Kara Calder, the senior director of programs at the museum, said.

To that end, the museum is staging its inaugural celebration of Juneteenth on June 19 with programming that focuses on what Calder described as “what the lives of Black individuals and families were like at that time,” with Black historic interpreters telling those stories.

Juneteenth marks the anniversary of the summer day in 1865 when federal troops enforced the emancipation of a quarter of a million enslaved people in Galveston, Texas — more than two years after the Emancipation Proclamation ended slavery. Word of emancipation hadn’t reached — or was ignored by — slaveholders in more geographically isolated areas of the country, until Union Major General Gordon Granger and his army stepped in.

Plans for a Juneteenth event at the museum were actually in motion for 2020, Calder said, but were placed on hold because of the pandemic.

The museum has tapped Black historic interpreters in the past as consultants and collaborators for specific projects. Some of the interpreters pose as prominent historical figures for special events.

Last year, for instance, the museum incorporated into its Yuletide Celebration event a scene about Watch Night, a late-night Christian service held on New Year’s Eve that commemorates when African Americans gathered in churches on New Year's Eve in 1862, to await the hour when the Emancipation Proclamation would take effect on January 1, 1863.

But museum officials acknowledge that these instances aren’t consistent enough to accurately represent what life was like for average people of color in this region.

A ‘LIVING MUSEUM’

Since its founding in 1966, Genesee Country Village & Museum has functioned as a “living history” museum, dedicated to preserving tangible history through the buildings and artifacts transported to the grounds from all over western New York, and to showcasing what life was like through the work of historic interpreters who interact with the visiting public.

The site feels like an authentic village, and there are many bits of the collections that stand out. There is George Eastman’s childhood home, a stately little structure built in 1840 in the rural Oneida County village of Waterville. There are the wedding outfits of Frederick Douglass and his second wife, Helen Pitts, which are currently on display in the museum’s gallery with information on the variety of ways that enslaved and newly-free Black people’s marriages were or were not recognized.

“The most important thing I always tell people when I'm doing presentations is it's the nameless and faceless that we have to pay homage to,” said David Shakes, the director of the Rochester theater troupe The North Star Players, who is one of a few Black historic interpreters who has a longstanding relationship with the museum.

He has consulted with regional and national historic organizations for decades, and portrayed Frederick Douglass and abolitionist and playwright William Wells Brown at Genesee Country Village many times over the years.

“We know Frederick Douglass, we know Harriet Tubman,” Shakes said. “We know some of the icons, but I like to take a moment to say, ‘Hey, there are people who did things to help other people and help causes that we will never know and we need to recognize and take a moment for that.’”

Representation of Black and Indigenous people isn’t a small issue at Genesee Country Village, particularly considering the breadth of the museum’s educational responsibilities. The museum annually hosts educational programs for between 18,000 and 20,000 schoolchildren; 4,000 to 5,000 of whom attend Rochester public schools, where 53 percent of students are Black and 33 percent are Hispanic.

“Certainly in our school programs we have diversity,” said the museum’s chief executive officer, Becky Wehle, who is the granddaughter of the village’s founder, John L. Wehle. “But then as we do better and engage more community partners, we will hopefully continue to attract a broader audience as well. ‘This was what western New York in the 19th-century was like, there were all different kinds of people here’ — our mission is to tell that story. And so that's where this ties back to giving a fuller picture of what the community looked like and what the activities that were going on were.”

There are some obstacles to inclusion, however. Funding is one of them, Wehle explained. A lot of government grants don’t cover seasonal or part-time employees that make up most of the historic interpreter staff.

“Our interpretation staff, aside from a handful of supervisors, are not year round, because we're only open from full time from Mother's Day until October,” she said. “So that that's a big part of the challenge as well. We have been trying to identify some of these barriers, and figure out: is there a way we could create a position that is potentially funded from the outside, that would allow someone to work year-round?”

Another challenge is what the museum can afford to pay its interpreters. Senior Director of Interpretation Brian Nagel said it is tough to attract people who might make more money elsewhere to drive to the edge of the county line to do seasonal work for minimum wage.

“Before I arrived, the museum got an (Institute of Museum and Library Services) grant for doing an interpretive master plan,” said Nagel, who has been with the museum since 2005. “So we brought in experts from various areas to try to develop a plan for how we wanted to move forward over time. And so we've been working at that a little bit. But certainly getting into a more diverse interpretation has been a challenge. Fighting for STEM, other kinds of activities, has been easier than trying to break that diversity barrier.”

A NOD TO REALITY

Genesee Country Village’s buildings and interpreters represent a wide period of time in western New York. The museum has one foot in the era when slavery was active in New York state, and the other in the time after 1827, when it was abolished.

On either side of that year, though, there were thousands of formerly enslaved fugitives living free-but-furtive in New York. Even after abolishment, slave catchers would descend on northern cities and villages in pursuit of fugitives, often in cahoots with police and judges.

Mention of this reality is vague at Genesee Country Village. A visitor might learn about the Underground Railroad, or hear mention of the Abolition movement and the support it had in area towns. But on a typical day visitors will find no substantial focus on Black people’s reality during these times.

The museum’s Juneteenth celebration is a nod to that reality.

Such commemorations have been gaining support locally and nationally the past few years. In 2020, Juneteenth became a state holiday in New York, New Jersey, and Virginia, and there’s an ongoing push for Congress to recognize it as a federal holiday.

Honoring Juneteenth, which takes place Saturday, June 19, from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., will include storytelling, poetry, activities, and education — from the mouths of Black historic interpreters — about what life was like for Black people in western New York when emancipation was complete.

Visitors will hear stories of prominent African American figures, including Shakes’s portrayal of William Wells Brown, but also see representation of average Black people living in western New York during the time when news of emancipation went national.

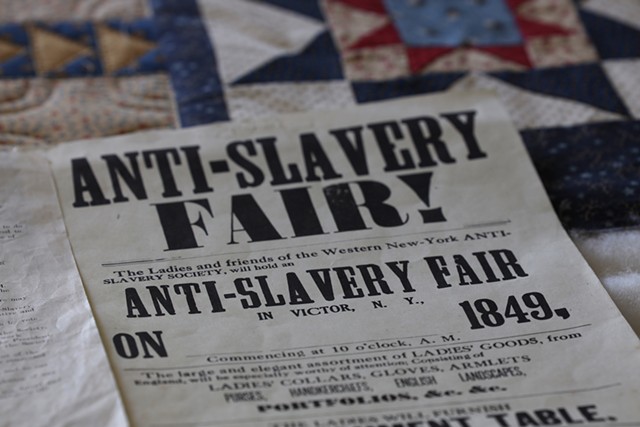

“A number of former enslaved individuals seeking family members would have posted notices, either broadsides on boards or notices in papers,” Calder said, adding that this aspect will be represented both in printed broadsides posted at the museum’s print shop, and through live interpretation of families seeking newly freed family members.

That’s where Cheyney McKnight comes in.

McKnight is another historic interpreter tapped by Genesee Country Village to present at Juneteenth. She’ll work with a small group of other interpreters to tell a story of what it may have been like for a newly emancipated southern Black family to encounter a northern Black family, in a time period when folks were seeking sold-off family members long separated from them.

“We have a tendency to really focus on extraordinary circumstances,” McKnight said of the typical focus on famous historic African Americans.

“The reality of the 19th-century in America is that the average Black person was enslaved,” McKnight said. “But we have other realities. Upstate New York had Black people who were free since the American Revolution. And so I wonder, when those Black people met Black people who were running away to the north . . . what were those interactions like, what were the cultural differences they encountered?”

Based in New York City, McKnight is a living historian who operates under the company name Not Your Momma’s History, and, like Shakes, has been involved in historic interpretation for many institutions and groups both locally and on a national level.

In her travels and collaborations, McKnight says she’s taken note of some institutions that are doing inclusion and representation well.

“The Whitney Plantation in Louisiana is just doing it so well,” she said. “The way in which they approach interpreters who should be interpreting. I had never before been to a plantation where they were really straight-up. And I think it's very important to have descendants of the enslaved community present in the conversation.”

Representation is important not only to paint a more complete portrait of life in 19th-century western New York, but also as an opportunity for discovery, Shakes said.

He said he’s witnessed audience members connect with material he presents on the Underground Railroad, sometimes sharing their small towns’ involvement in the clandestine network of safe houses and routes.

“We're still learning things,” Shakes said.

Rebecca Rafferty is CITY's life editor and can be reached at [email protected].

Speaking of...

-

Midwinter family activities to cure cabin fever

Feb 25, 2022 -

Forging a festival for Black theater

Feb 9, 2022 -

Cultural institutions join forces to draw summer tourists

May 28, 2021 - More »

Latest in Culture

More by Rebecca Rafferty

-

Beyond folklore

Apr 4, 2024 -

Partnership perks: Public Provisions @ Flour City Bread

Feb 24, 2024 -

Raison d’Art

Feb 19, 2024 - More »