[

{

"name": "500x250 Ad",

"insertPoint": "5",

"component": "15667920",

"parentWrapperClass": "",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

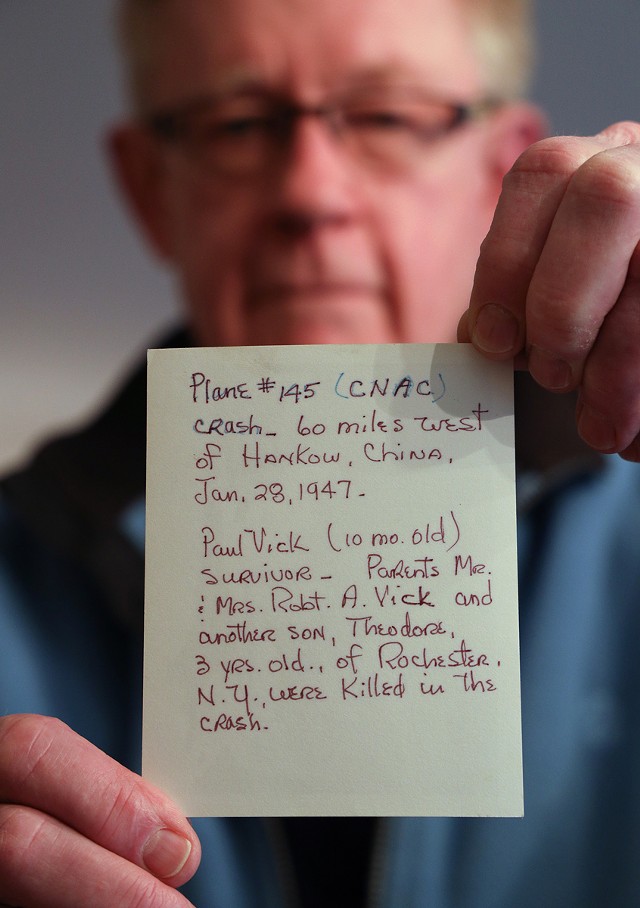

Paul Vick was just 16 months old on Jan. 28, 1947, when he fell from a clear blue sky into a cotton field in a remote region of China clasped in his father’s arms.

A few hours earlier, he and his parents and 3-year-old brother Teddy had boarded a China National Aviation Corporation airliner in Shanghai bound for Chongqing, where his father and mother were to carry out a commitment as Baptist missionaries.

About 40 minutes into the second leg of the flight, the left engine exploded and the wing fell off over a village about 90 miles west of Hankou. The plane, a twin-engine C-46 wartime cargo aircraft converted to ferry passengers, began spinning violently toward the earth in flames.

During the descent, as the story has been recounted to Vick, a crewmember managed to open a rear hatch. Luggage and people were sucked out of the plane. Clutching the fuselage and their children, Vick's parents, Robert and Dorothy Vick, watched the ground rapidly approaching and saw no alternative.

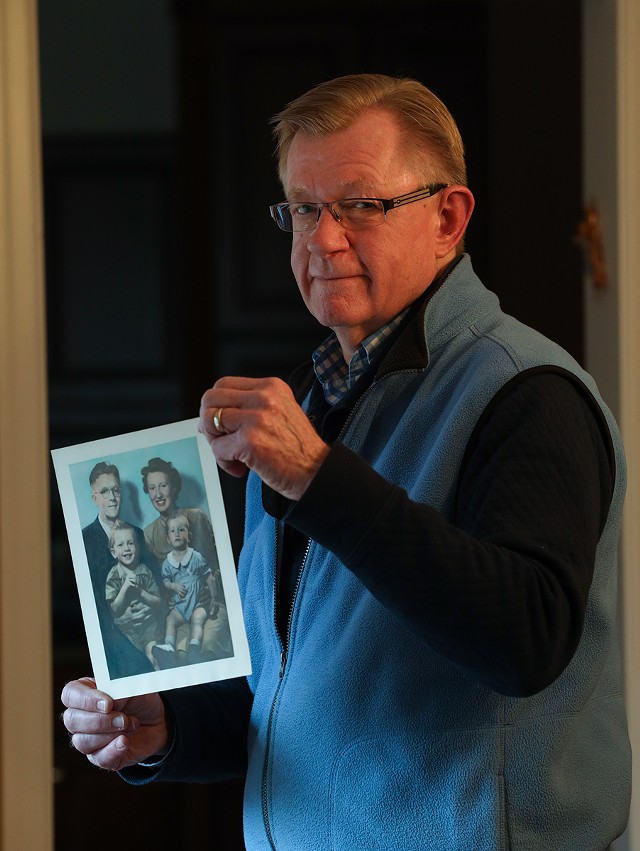

“My mother grabbed my brother and I was grabbed by my father, and jumped,” said Vick, now 77, who spoke from the dining room table in his Brighton home strewn with memorabilia related to the disaster.

Below, villagers watched the fiery aircraft hurtle toward their cotton field, spewing items and bodies along the way. Repelled by the heat of the burning wreckage after it crashed, they searched their surroundings for survivors.

They would find none, save for a man groaning in pain and a toddler lying quietly beside him in mud with his eyes open. Vick and his father were the only survivors among the 26 people on board.

“Everybody else on the plane, if they stayed on the plane, they were burned,” Vick said. “But if they were able to have gotten out, they died instantaneously from the jump. My mother was found holding my brother.”

Dorothy Vick was 25 years old.

Villagers took Robert, who was 29, to a medicine man. They brought Vick to a woman whose own infant had recently died and could nourish him with breastmilk. Father and son were eventually transported to a small Catholic mission hospital.

Robert, suffering from extensive internal injuries, would die there three days later, but not before being presented with his son and telling a priest that the boy was to be raised by his paternal grandparents in his hometown of Rochester.

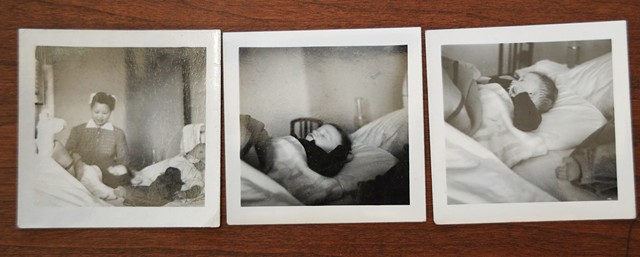

Incredibly, Vick’s injuries were relatively superficial: two broken legs, partial facial paralysis, singed hair, and cuts and bruises. His legs were put into traction for about two months.

“I didn’t really show any other signs of the accident,” Vick said. “The observation that almost everyone that saw me there made was how happy I looked, you know, that I was joking around with the nurses . . . When I was with my father, something must have happened there because I hadn’t uttered a word. I hadn’t uttered a sound.

“There’s a lot of mystery in life that we don’t understand,” he went on. “As my grandfather, my mother’s dad, always said, ‘We may not understand now, but someday we will.’”

Vick chronicled the crash, his recuperation, and the life he went on to live — from growing up in the charge of his grandparents on Harvard Street, to graduating from the seminary and law school, to becoming a grandfather of seven — in a memoir, “Where the Cotton Grows,” which he self-published in 2021.

He is from a prominent Rochester family, a relation of the wealthy horticulturalist and seedsman James Vick, who built a racetrack on what are now the streets Vick Park A and Vick Park B.

But Vick attained a reluctant fame all his own from the tragedy.

News of the crash and his survival made newspapers around the world. For years, any mention of him in the press was preceded by phrases like “air crash baby” and “orphan.” A Wikipedia page lists him as tied for the youngest sole survivor of a plane crash. (A 14-month-old boy set the record when he was the only passenger to survive a crash in Vietnam in 1997.)

During Vick's return to Rochester in April 1947 following his recovery, he was by chance on a flight with Frank Sinatra. The crooner, having read about the boy, was so moved by the story that he bought Vick a toy stuffed elephant during a layover. Vick named the doll “Frankie.”

A retired family and estate lawyer at the firm of Phillips Lytle and an ordained American Baptist minister who is the treasurer for the board of International Ministries, a Baptist missionary society, Vick said his memoir was ultimately about hope.

He spoke about his book a couple weeks before the 76th anniversary of the crash. The conversation has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Q: Your book is “Where the Cotton Grows.” What’s the significance of the title?

The field that the plane crashed into was a cotton field; also had rice paddies. And, when we went back, there was primarily cotton. The symbolism of this to me was significant because here is land that experienced great tragedy, which had become a part of the fabric of that village, by the way, that constantly renews itself every year. There is new life, new growth, and a place of great tragedy also has seen rebirth.

Q: Why write this book? Why now?

Over the years, as people who knew about this story talked to me about it, they kept saying, ‘Look, this is a significant story. You need to tell it for posterity sake as well as the book could be helpful to others.’ You can’t name an individual or family that hasn’t experienced tragedy in their lives. And how do people handle that tragedy? What do they do with that tragedy? My family had a way of responding to tragedy that didn’t focus on the tragedy itself but focused on what you do with that tragedy. Also, it’s a way of acknowledging the impact that International Ministries, the organization I’m involved with, has had over the last 200-plus years, much of the work in Asia.

Q: As part of your preparation for the book, but also as part of your life journey, you visited the crash site and where you believed your family to be buried. What was that experience like for you?

That was profound. You know, as well as being on the crash site itself, and probably the crash site more so, recognizing that this happened there, and this is where they died, not just them, but everyone that was on that plane. . . . But to think of that violent act of the plane crashing and taking the lives of all these people, Chinese and American and Canadian, that sense was overwhelming. But then, to take a look at a field growing cotton that was growing out of this. You know, blood had been spilled on the land, but new growth was happening.

Q: How did your family memorialize the anniversary of the accident when you were growing up, if at all?

The only reference to that was we would make sure that flowers were on the altar of the church to commemorate that date. So, there was ongoing acknowledgement down through the years of that date, but it really wasn’t, you know, it wasn’t a sad occasion. The loss was deeply felt. You know, shortly before my grandfather died, he and I had an opportunity to be alone to talk about just whatever he wanted to talk about, and for the first time in my life, I saw tears coming out of his eyes, and he said, “I can still feel your mother crashing to the ground.” Now, you would never have known that. He had an amazing disposition. He was always upbeat, always the optimist, always trying to make each moment a better moment for people. Acknowledging that situation was a part of our lives, but the focus was what you do with that.

Q: Is there any way you memorialize the day today?

Not other than an acknowledgement to myself. You know, the next generations they’re too far removed. So, it’s not really something I focus on. This year on the 28th I will be in India, and I’m in India doing work that I think is consistent with the kind of work my father would do.

(Vick will be helping establish educational resources in marginalized communities.)

Q: You were given this extraordinary gift of life through an act of heroism by your father. Did you ever feel pressure to live up to be the boy and the man that you maybe imagined he hoped you would be?

It’s interesting, because if you follow my path, my life trajectory, in many ways it parallels his. . . . Is that because I was fulfilling his life’s path? I suppose that could be part of it. But in a real sense, I feel it’s my own path. Because what I do and how I do it is so different from how he did what he did. . . . Writing this book was very cathartic for me. I became at times very tearful bringing forward a lot of this very personal story of my family. . . . But, you know, I think it also gave me an opportunity to tell my story and not his story or my mother’s story. This is my story and how maybe some of the ways that my life had been influenced by them in a very real sense. And maybe this is part of it: I’ve never really felt that my mother and father are gone. They’re still a part of my life.

Q: What do you hope people get out of the book?

I think if there was one word it’s hope. All of us face tragedies in life. What do you do with those? My granddaughter, Emma, died at 2-and-a-half years of age.

Q: You dedicated the book to her.

She was an amazing girl, and again, unable to live a life, so somebody else has to tell her story. So, I tell her story every chance I get. . . . Everyone is special. Everyone is unique. Everyone has gifts. Everyone has something that they can give that would help all of us. For those who feel hopeless. For those who feel that they do not have worth or value. My hope is that this book might be able to touch them in some way to begin to think about the fact that they are a sacred person, and that they are loved. I think that's the other thing: It's a really a story of love, you know? It’s a family of love. I was born into a family of love. That has been a part of how I engaged others.

David Andreatta is CITY's editor. He can be reached at [email protected].

A few hours earlier, he and his parents and 3-year-old brother Teddy had boarded a China National Aviation Corporation airliner in Shanghai bound for Chongqing, where his father and mother were to carry out a commitment as Baptist missionaries.

About 40 minutes into the second leg of the flight, the left engine exploded and the wing fell off over a village about 90 miles west of Hankou. The plane, a twin-engine C-46 wartime cargo aircraft converted to ferry passengers, began spinning violently toward the earth in flames.

During the descent, as the story has been recounted to Vick, a crewmember managed to open a rear hatch. Luggage and people were sucked out of the plane. Clutching the fuselage and their children, Vick's parents, Robert and Dorothy Vick, watched the ground rapidly approaching and saw no alternative.

“My mother grabbed my brother and I was grabbed by my father, and jumped,” said Vick, now 77, who spoke from the dining room table in his Brighton home strewn with memorabilia related to the disaster.

Below, villagers watched the fiery aircraft hurtle toward their cotton field, spewing items and bodies along the way. Repelled by the heat of the burning wreckage after it crashed, they searched their surroundings for survivors.

They would find none, save for a man groaning in pain and a toddler lying quietly beside him in mud with his eyes open. Vick and his father were the only survivors among the 26 people on board.

“Everybody else on the plane, if they stayed on the plane, they were burned,” Vick said. “But if they were able to have gotten out, they died instantaneously from the jump. My mother was found holding my brother.”

Dorothy Vick was 25 years old.

Villagers took Robert, who was 29, to a medicine man. They brought Vick to a woman whose own infant had recently died and could nourish him with breastmilk. Father and son were eventually transported to a small Catholic mission hospital.

Robert, suffering from extensive internal injuries, would die there three days later, but not before being presented with his son and telling a priest that the boy was to be raised by his paternal grandparents in his hometown of Rochester.

Incredibly, Vick’s injuries were relatively superficial: two broken legs, partial facial paralysis, singed hair, and cuts and bruises. His legs were put into traction for about two months.

“I didn’t really show any other signs of the accident,” Vick said. “The observation that almost everyone that saw me there made was how happy I looked, you know, that I was joking around with the nurses . . . When I was with my father, something must have happened there because I hadn’t uttered a word. I hadn’t uttered a sound.

“There’s a lot of mystery in life that we don’t understand,” he went on. “As my grandfather, my mother’s dad, always said, ‘We may not understand now, but someday we will.’”

Vick chronicled the crash, his recuperation, and the life he went on to live — from growing up in the charge of his grandparents on Harvard Street, to graduating from the seminary and law school, to becoming a grandfather of seven — in a memoir, “Where the Cotton Grows,” which he self-published in 2021.

He is from a prominent Rochester family, a relation of the wealthy horticulturalist and seedsman James Vick, who built a racetrack on what are now the streets Vick Park A and Vick Park B.

But Vick attained a reluctant fame all his own from the tragedy.

News of the crash and his survival made newspapers around the world. For years, any mention of him in the press was preceded by phrases like “air crash baby” and “orphan.” A Wikipedia page lists him as tied for the youngest sole survivor of a plane crash. (A 14-month-old boy set the record when he was the only passenger to survive a crash in Vietnam in 1997.)

During Vick's return to Rochester in April 1947 following his recovery, he was by chance on a flight with Frank Sinatra. The crooner, having read about the boy, was so moved by the story that he bought Vick a toy stuffed elephant during a layover. Vick named the doll “Frankie.”

A retired family and estate lawyer at the firm of Phillips Lytle and an ordained American Baptist minister who is the treasurer for the board of International Ministries, a Baptist missionary society, Vick said his memoir was ultimately about hope.

He spoke about his book a couple weeks before the 76th anniversary of the crash. The conversation has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Q: Your book is “Where the Cotton Grows.” What’s the significance of the title?

The field that the plane crashed into was a cotton field; also had rice paddies. And, when we went back, there was primarily cotton. The symbolism of this to me was significant because here is land that experienced great tragedy, which had become a part of the fabric of that village, by the way, that constantly renews itself every year. There is new life, new growth, and a place of great tragedy also has seen rebirth.

Q: Why write this book? Why now?

Over the years, as people who knew about this story talked to me about it, they kept saying, ‘Look, this is a significant story. You need to tell it for posterity sake as well as the book could be helpful to others.’ You can’t name an individual or family that hasn’t experienced tragedy in their lives. And how do people handle that tragedy? What do they do with that tragedy? My family had a way of responding to tragedy that didn’t focus on the tragedy itself but focused on what you do with that tragedy. Also, it’s a way of acknowledging the impact that International Ministries, the organization I’m involved with, has had over the last 200-plus years, much of the work in Asia.

Q: As part of your preparation for the book, but also as part of your life journey, you visited the crash site and where you believed your family to be buried. What was that experience like for you?

That was profound. You know, as well as being on the crash site itself, and probably the crash site more so, recognizing that this happened there, and this is where they died, not just them, but everyone that was on that plane. . . . But to think of that violent act of the plane crashing and taking the lives of all these people, Chinese and American and Canadian, that sense was overwhelming. But then, to take a look at a field growing cotton that was growing out of this. You know, blood had been spilled on the land, but new growth was happening.

Q: How did your family memorialize the anniversary of the accident when you were growing up, if at all?

The only reference to that was we would make sure that flowers were on the altar of the church to commemorate that date. So, there was ongoing acknowledgement down through the years of that date, but it really wasn’t, you know, it wasn’t a sad occasion. The loss was deeply felt. You know, shortly before my grandfather died, he and I had an opportunity to be alone to talk about just whatever he wanted to talk about, and for the first time in my life, I saw tears coming out of his eyes, and he said, “I can still feel your mother crashing to the ground.” Now, you would never have known that. He had an amazing disposition. He was always upbeat, always the optimist, always trying to make each moment a better moment for people. Acknowledging that situation was a part of our lives, but the focus was what you do with that.

Q: Is there any way you memorialize the day today?

Not other than an acknowledgement to myself. You know, the next generations they’re too far removed. So, it’s not really something I focus on. This year on the 28th I will be in India, and I’m in India doing work that I think is consistent with the kind of work my father would do.

(Vick will be helping establish educational resources in marginalized communities.)

Q: You were given this extraordinary gift of life through an act of heroism by your father. Did you ever feel pressure to live up to be the boy and the man that you maybe imagined he hoped you would be?

It’s interesting, because if you follow my path, my life trajectory, in many ways it parallels his. . . . Is that because I was fulfilling his life’s path? I suppose that could be part of it. But in a real sense, I feel it’s my own path. Because what I do and how I do it is so different from how he did what he did. . . . Writing this book was very cathartic for me. I became at times very tearful bringing forward a lot of this very personal story of my family. . . . But, you know, I think it also gave me an opportunity to tell my story and not his story or my mother’s story. This is my story and how maybe some of the ways that my life had been influenced by them in a very real sense. And maybe this is part of it: I’ve never really felt that my mother and father are gone. They’re still a part of my life.

Q: What do you hope people get out of the book?

I think if there was one word it’s hope. All of us face tragedies in life. What do you do with those? My granddaughter, Emma, died at 2-and-a-half years of age.

Q: You dedicated the book to her.

She was an amazing girl, and again, unable to live a life, so somebody else has to tell her story. So, I tell her story every chance I get. . . . Everyone is special. Everyone is unique. Everyone has gifts. Everyone has something that they can give that would help all of us. For those who feel hopeless. For those who feel that they do not have worth or value. My hope is that this book might be able to touch them in some way to begin to think about the fact that they are a sacred person, and that they are loved. I think that's the other thing: It's a really a story of love, you know? It’s a family of love. I was born into a family of love. That has been a part of how I engaged others.

David Andreatta is CITY's editor. He can be reached at [email protected].