[

{

"name": "500x250 Ad",

"insertPoint": "5",

"component": "15667920",

"parentWrapperClass": "",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

Everybody makes a bad decision once in a while.

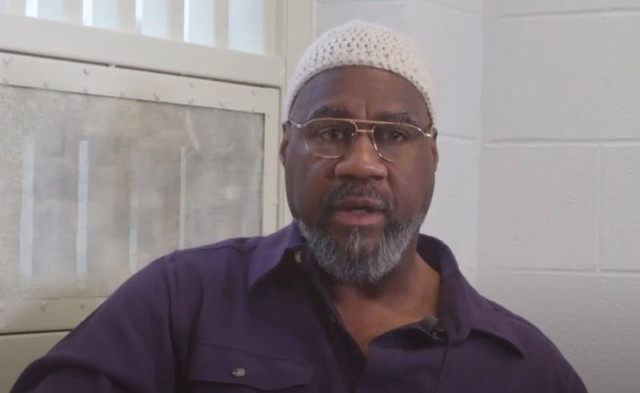

Anthony Bottom made one in 1971 when he took part in the shooting deaths of two New York City police officers outside a Harlem housing project.

He and two other men, all members of the Black Liberation Army, an underground militant offshoot of the Black Panther Party, were convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to 25 years-to-life in prison. He was 19 years old at the time of the crime.

Sandra Doorley, the Monroe County district attorney, made a bad decision in October, when she charged Bottom with felonies related to him illegally registering to vote. Continuing the prosecution will only make it worse.

Not that Bottom, who lives in Brighton under the name he assumed in prison, Jalil Abdul Muntaqim, didn’t attempt to register to vote. He did. He filled out the paperwork on Oct. 8, a day after he was released from prison on parole.

The problem with his timing was that parolees in New York are allowed to vote only upon receiving a conditional pardon from the governor that restores their voting rights — and Muntaqim hadn’t received that pardon.

Gov. Andrew Cuomo has issued such pardons as a matter of course on a monthly basis since 2018, when he signed an executive order directing the commissioner of the state Department of Corrections and Community Supervision to submit to the governor each month a list of every felon newly eligible for parole, with each name to be “given consideration for a conditional pardon that will restore voting rights.”

Anyone on the list would be eligible for a pardon as long as they weren’t flagged for any specific concern. Most parolees receive their pardon within four to six weeks of their release. The pardon doesn’t expunge their record or restore other rights stripped from them, such as the right to own a gun.

Cuomo denied Muntaqim a pardon when his name came up for consideration in November, spokespeople for the governor and the Department of Corrections said.

By then, Muntaqim had already been arraigned on felony charges of tampering with public records and offering a false instrument for filing, which carry maximum penalties of seven years and four years in prison, respectively. He is scheduled to appear next in Brighton Town Court on Dec. 14.

If convicted, Muntaqim will likely return to prison and die there. He is 69 years old.

Not that Muntaqim’s fate matters much to a lot of people.

The concept of disenfranchising felons dates to colonial days, when certain criminals were stripped of rights in a practice known as civil death. Later Americans applied their own uniquely racist twist to the practice after the Civil War, when many states used it to deprive Black men of the vote they had recently gained.

Today, the impact of these laws still falls disproportionately on poor people of color.

The Supreme Court interprets the Constitution in such a way that upholds these restrictions, which are a confusing patchwork of laws that vary by state.

Forty-eight states prohibit current inmates from voting and 30 keep parolees from the polls, according to the Sentencing Project, an advocacy group for criminal justice reform. Indeed, if Muntaqim resided in 20 other states, he wouldn’t be in this predicament.

“The laws are different from state to state, they’re very confusing, and the penalties for these offenses are extreme and unconscionable,” Nicole Porter, the director of advocacy at the Sentencing Project, said. “I don’t know how these prosecutors sleep at night.”

A national movement to restore voting rights to formerly incarcerated people is gaining steam, though.

Advocates say restoring voting rights to former felons helps them shed the stigma of criminal conviction and empowers them to be responsible citizens with a voice in their community.

But many conservative groups oppose the movement. They point out that supporters often make no mention of restoring other rights, such as the right to own a gun, suggesting that the push is really just about getting the votes of felons.

“You lose many other rights besides your right to vote when you are convicted of a felony,” said Hans von Spakovsky, a lawyer at the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank that tracks voting prosecutions. “Yet many of those moving for immediate restoration of the ability to vote when a felon steps out of prison don’t seem very concerned about restoring those rights.”

They have a point. The movement to expand access to the vote has become a political hot potato, with Republicans opposing it and Democrats tending to support it, in part because they stand to gain the most from it.

Perhaps not surprisingly, then, it was the head of the Monroe County Republican Party, William Napier, who alerted Doorley to Muntaqim’s registration, which was filed under his birth name. Napier even called a news conference for the occasion.

The case was a gimme for Doorley, who is also a Republican. That Muntaqim attempted to register to vote is so clear it doesn’t require the qualifier “allegedly” here.

Whether he did it with intent to defraud, which is required for the charges to stick, is another matter, however.

It is absurd to think that a man who spent nearly 50 years behind bars would be so hellbent on casting a ballot in a single election as to jeopardize his newfound freedom on Day One. It seems obvious that Muntaqim didn’t know what he was doing when he filled out that form.

Muntaqim and his lawyer, a public defender, wouldn’t comment on his circumstances. But his mother has cast his actions as “a mistake,” saying the voter registration form was in “a packet of papers that was issued to him to help him assimilate himself back into society.”

Friends of Muntaqim said that packet was given to him by the county’s Department of Human Services, which helps newly released prisoners acclimate. Those packets include everything a former inmate might need — information on Medicaid, food stamps, child care, becoming an organ donor, and a voter registration form.

“I don’t think he was trying to game the system” by signing the form, said James Schuler, who has known Muntaqim since they met as inmates at Auburn Correctional Facility in 2000. “One thing he wanted to be more than anything was a productive member of society. They gave him paperwork to do that and he signed.”

Schuler, 52, described Muntaqim as “a leader” and “a peacekeeper” in prison, where he earned college degrees and mentored inmates.

After nearly 50 years of incarceration, Muntaqim corrected his bad decision to the extent he could. The New York Board of Parole recognized that when it deemed him ready to return to society, having taken into consideration his disciplinary record, personal growth, and the severity of his crimes.

Doorley said in an interview that her charges against him have nothing to do with his criminal past. She said they were about answering allegations of voter fraud in the weeks before the election and that Muntaqim’s case seemed straightforward.

“Is it a major thing?” she asked of the charges. “No.”

Not to her, but the stakes for Muntaqim are life-changing at a time when the nation is changing to recognize the implications of disenfranchising people who look like him.

Asked if she would consider dropping the charges, Doorley replied, “I don’t think we’ve ruled anything out. It’s not like we’re rushing to a grand jury. Obviously, we may consider making some plea offer.”

Now it’s Doorley turn to correct her bad decision.

David Andreatta is CITY's editor. He can be reached at [email protected].

Anthony Bottom made one in 1971 when he took part in the shooting deaths of two New York City police officers outside a Harlem housing project.

He and two other men, all members of the Black Liberation Army, an underground militant offshoot of the Black Panther Party, were convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to 25 years-to-life in prison. He was 19 years old at the time of the crime.

Sandra Doorley, the Monroe County district attorney, made a bad decision in October, when she charged Bottom with felonies related to him illegally registering to vote. Continuing the prosecution will only make it worse.

Not that Bottom, who lives in Brighton under the name he assumed in prison, Jalil Abdul Muntaqim, didn’t attempt to register to vote. He did. He filled out the paperwork on Oct. 8, a day after he was released from prison on parole.

The problem with his timing was that parolees in New York are allowed to vote only upon receiving a conditional pardon from the governor that restores their voting rights — and Muntaqim hadn’t received that pardon.

Gov. Andrew Cuomo has issued such pardons as a matter of course on a monthly basis since 2018, when he signed an executive order directing the commissioner of the state Department of Corrections and Community Supervision to submit to the governor each month a list of every felon newly eligible for parole, with each name to be “given consideration for a conditional pardon that will restore voting rights.”

Anyone on the list would be eligible for a pardon as long as they weren’t flagged for any specific concern. Most parolees receive their pardon within four to six weeks of their release. The pardon doesn’t expunge their record or restore other rights stripped from them, such as the right to own a gun.

Cuomo denied Muntaqim a pardon when his name came up for consideration in November, spokespeople for the governor and the Department of Corrections said.

By then, Muntaqim had already been arraigned on felony charges of tampering with public records and offering a false instrument for filing, which carry maximum penalties of seven years and four years in prison, respectively. He is scheduled to appear next in Brighton Town Court on Dec. 14.

If convicted, Muntaqim will likely return to prison and die there. He is 69 years old.

Not that Muntaqim’s fate matters much to a lot of people.

The concept of disenfranchising felons dates to colonial days, when certain criminals were stripped of rights in a practice known as civil death. Later Americans applied their own uniquely racist twist to the practice after the Civil War, when many states used it to deprive Black men of the vote they had recently gained.

Today, the impact of these laws still falls disproportionately on poor people of color.

The Supreme Court interprets the Constitution in such a way that upholds these restrictions, which are a confusing patchwork of laws that vary by state.

Forty-eight states prohibit current inmates from voting and 30 keep parolees from the polls, according to the Sentencing Project, an advocacy group for criminal justice reform. Indeed, if Muntaqim resided in 20 other states, he wouldn’t be in this predicament.

“The laws are different from state to state, they’re very confusing, and the penalties for these offenses are extreme and unconscionable,” Nicole Porter, the director of advocacy at the Sentencing Project, said. “I don’t know how these prosecutors sleep at night.”

A national movement to restore voting rights to formerly incarcerated people is gaining steam, though.

Advocates say restoring voting rights to former felons helps them shed the stigma of criminal conviction and empowers them to be responsible citizens with a voice in their community.

But many conservative groups oppose the movement. They point out that supporters often make no mention of restoring other rights, such as the right to own a gun, suggesting that the push is really just about getting the votes of felons.

“You lose many other rights besides your right to vote when you are convicted of a felony,” said Hans von Spakovsky, a lawyer at the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank that tracks voting prosecutions. “Yet many of those moving for immediate restoration of the ability to vote when a felon steps out of prison don’t seem very concerned about restoring those rights.”

They have a point. The movement to expand access to the vote has become a political hot potato, with Republicans opposing it and Democrats tending to support it, in part because they stand to gain the most from it.

Perhaps not surprisingly, then, it was the head of the Monroe County Republican Party, William Napier, who alerted Doorley to Muntaqim’s registration, which was filed under his birth name. Napier even called a news conference for the occasion.

The case was a gimme for Doorley, who is also a Republican. That Muntaqim attempted to register to vote is so clear it doesn’t require the qualifier “allegedly” here.

Whether he did it with intent to defraud, which is required for the charges to stick, is another matter, however.

It is absurd to think that a man who spent nearly 50 years behind bars would be so hellbent on casting a ballot in a single election as to jeopardize his newfound freedom on Day One. It seems obvious that Muntaqim didn’t know what he was doing when he filled out that form.

Muntaqim and his lawyer, a public defender, wouldn’t comment on his circumstances. But his mother has cast his actions as “a mistake,” saying the voter registration form was in “a packet of papers that was issued to him to help him assimilate himself back into society.”

Friends of Muntaqim said that packet was given to him by the county’s Department of Human Services, which helps newly released prisoners acclimate. Those packets include everything a former inmate might need — information on Medicaid, food stamps, child care, becoming an organ donor, and a voter registration form.

“I don’t think he was trying to game the system” by signing the form, said James Schuler, who has known Muntaqim since they met as inmates at Auburn Correctional Facility in 2000. “One thing he wanted to be more than anything was a productive member of society. They gave him paperwork to do that and he signed.”

Schuler, 52, described Muntaqim as “a leader” and “a peacekeeper” in prison, where he earned college degrees and mentored inmates.

After nearly 50 years of incarceration, Muntaqim corrected his bad decision to the extent he could. The New York Board of Parole recognized that when it deemed him ready to return to society, having taken into consideration his disciplinary record, personal growth, and the severity of his crimes.

Doorley said in an interview that her charges against him have nothing to do with his criminal past. She said they were about answering allegations of voter fraud in the weeks before the election and that Muntaqim’s case seemed straightforward.

“Is it a major thing?” she asked of the charges. “No.”

Not to her, but the stakes for Muntaqim are life-changing at a time when the nation is changing to recognize the implications of disenfranchising people who look like him.

Asked if she would consider dropping the charges, Doorley replied, “I don’t think we’ve ruled anything out. It’s not like we’re rushing to a grand jury. Obviously, we may consider making some plea offer.”

Now it’s Doorley turn to correct her bad decision.

David Andreatta is CITY's editor. He can be reached at [email protected].