[

{

"name": "500x250 Ad",

"insertPoint": "5",

"component": "15667920",

"parentWrapperClass": "",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

The earliest blooms of police reform in Rochester, measures intended to address ills that still haunt the city today, sprung from what is now a vacant lot on Thurston Road on a November night in 1975.

There, in a basement unit of what was then the Apollo Apartments, a teenage mother argued with her husband, who was said to have had a thing for pushing her around. That night, 18-year-old Denise Hawkins would be pushed so far she would wind up dead.

The argument got physical, as it often did, and the couple tussled into the kitchen, where Hawkins brandished a knife and slashed her husband’s cheek. Minutes later, there was a pounding at the front door.

“Police!” an officer yelled from the other side, the door reportedly bowing outward from the battering inside.

“Look out, she’s coming out with a knife!” the husband shouted.

Hawkins, still gripping the knife tightly in her hand, spilled into the exterior hallway, where two officers awaited with guns drawn. “Drop it!” the officers shouted in unison.

She took two more steps before one of the officers, Michael Leach, a 22-year-old rookie, put a bullet in her chest, killing her instantly.

The circumstances of her death and its aftermath are familiar: Hawkins was Black, Leach was white and on duty, and the Black community erupted at the idea of another white cop being too quick to the pull the trigger on a person of color.

Leach would be exonerated by a grand jury and go on to retire from the Rochester Police Department as a captain nearly 30 years later. He would, however, wind up doing a stretch in jail at one point in retirement for fatally shooting his own son in the motel room they shared after mistaking him for an intruder.

Outrage over Hawkins’ death and what was regarded by many to be a sham of an investigation into Leach moved City Council to appoint a blue-ribbon panel to examine how policing in Rochester could improve. The Citizens Committee on Police Affairs, dubbed the Crimi Committee after its chairman and local lawyer Charles Crimi, would recommend sweeping changes to the Rochester Police Department.

Most of the changes would ostensibly be adopted, at least on paper.

Yet now, a new task force is asking the same questions about policing that were raised and supposedly addressed by the Crimi Committee nearly a half-century ago, including matters of domestic disputes, recruitment, neighborhood relations, psychological testing of officers, and firearms training.

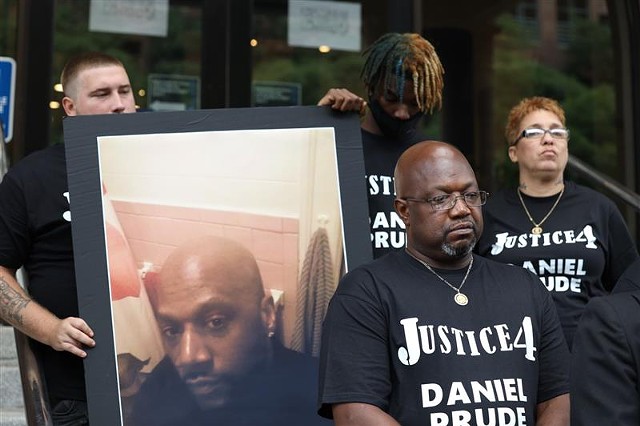

Those questions became all the more relevant this week with news that 41-year-old Daniel Prude died of asphyxiation after being restrained by Rochester police officers in March.

Evolutions in policing and the city offer the task force new ground to mine. But the similarities between Hawkins’ death and those of so many people of color at the hands of police in Rochester and elsewhere around the country in the decades since, have task force members revisiting old ground for whether the Crimi Commission recommendations worked or, worse, whether they were implemented at all.

“That’s the right question,” said Bill Johnson, the former mayor of Rochester and a co-chair of the new Racial and Structural Equity (RASE) Commission.

“There’s a lot of stuff that’s happened in the community, and what’s important is for us to not only know what happened, but what didn’t,” Johnson said. “Did any change materialize as a result of all of this work? Did these recommendations get phased out, or upgraded?”

NINETY-SEVEN RECOMMENDATIONS

The RASE Commission, a joint initiative of the administrations of Rochester Mayor Lovely Warren and Monroe County Executive Adam Bello, is less a police reform task force than it is an ambitiously broad effort to identify and address the roots of structural racism.

The commission, a panel of 21 people led by Johnson along with Muhammad Shafiq, a religious studies professor at Nazareth College, and Arline Santiago, a senior vice president at ESL Federal Credit Union, is expected to publish a report on its findings early next year. The report is supposed to touch on topics as varied as education, equitable housing, business development, and policing.

On the latter, Johnson has been there before; he served on the Crimi Committee and led his own program as mayor in 2004 called Pathways to Better Police-Community Relations.

“There were real changes in reporting and policy that came as the result of that (Crimi Committee) document, and that’s over 40 years old,” Johnson said in a phone interview. “That’s my benchmark.”

The Crimi Committee made 97 recommendations, 85 of which were approved by the City Council in 1977. A descendant of those recommendations is the fledgling Police Accountability Board, which evolved from a recommendation that internal police investigations into alleged officer misconduct include examination by a civilian review panel. The so-called Complaint Investigation Committee, for the first time, added a lone civilian to the misconduct review process.

But many of the Crimi Committee’s recommendations appear to have gone nowhere.

For instance, the committee called for officers to be better educated, citing a 1973 National Advisory Commission recommendation that all police officers by 1978 should have three years of college education.

The RPD currently requires its officers to have a high school diploma or equivalent.

The committee also noted that recruiting minority candidates would go a long way toward building credibility in city neighborhoods, and recommended “seriously considering” requiring officers to live in the city as a condition of their employment.

The city charter requires employees in the uppermost tiers of city government to live in Rochester, but carves out an exception for first responders. The state Public Officers Law exempts police officers and firefighters from municipal residency requirements. The most the city can require is that officers live in Monroe County or one of its five adjacent counties.

By the time Johnson launched his Pathways program, 28.5 percent of the RPD force was minority. Today, just 13 percent of Rochester police officers are non-white, and less than 15 percent live in the city, according to the RPD’s official roster.

Then there’s the Family Crisis Intervention (FACIT) program. FACIT is a mobile team made up of social work professionals designated to respond to domestic violence, attempted suicides, family crises, mental health calls, rapes, child abuse, and other issues where a social element is at play.

The Crimi Committee recommended that FACIT receive more support, and specifically called on the City Council to take steps to fully fund the program and expand it, if necessary.

When that recommendation was made in 1977, FACIT had eight social workers. Today, the team has 10 and was estimated to have taken 3,500 calls last year, when domestic violence complaints alone accounted for nearly 30,000 of the RPD’s calls for service.

MENTAL HEALTH A PRIORITY

There is little agreement between police and reform advocates about what change could and should look like. Where there is common ground, however, is in the belief that police should not be the first resort for mental health crises.

“There’s certain things we don’t want police officers learning as they go,” said Rochester Police Chief La’Ron Singletary. “There’s no amount of training I can offer, outside of policing, that is going to equate to what a social worker has or what a family therapist or mental health therapist has.”

One model for handling mental health calls that has caught the attention of some city officials and reform advocates is something called CAHOOTS, a nonprofit mobile crisis intervention program out of Eugene, Oregon. Instead of police being deployed to calls for service for mental health crises such as welfare checks, disorientation, and non-violent disputes, the program mobilizes two-person teams of a medic and a social worker.

“The last few incidents that involved someone in crisis, from viewing body camera footage, have been escalated primarily by the officers showing up on the scene,” said City Council member Mary Lupien. “They end up hurting the person by their escalation and lack of awareness of mental health issues.”

This is not a new revelation. The Crimi Committee highlighted family crises as among those situations that have the most potential to spiral out of control and become dangerous. Likewise, a report from the non-profit Treatment Advocacy Center said people with untreated mental illness are 16 times more likely to be killed by police than people without mental illness.

Monroe County Sheriff Todd Baxter lamented that police so often get dispatched to such situations and blamed what he called a societal “addiction to 911.”

“We’re the quickest form of government, and we’ve been asked to solve a lot of the world’s problems with a 911 phone call,” Baxter said. “Which, in some of those situations, a police officer, or a police department, is not designed to solve those problems.”

The Crimi Committee touched on that decades ago, pointing out that, at the time, just 10 percent of police activities were related to enforcing the law. The remainder of their time was spent responding to service calls.

IF ALL YOU HAVE IS A HAMMER . . .

Nearly eight years to the day after Hawkins was shot and killed, another young Black mother was fatally shot by Rochester police.

Alecia McCuller was just 21 years old when she was shot twice in the chest by Officer Thomas Whitmore. McCuller was allegedly wielding a knife and attempting to stab her boyfriend outside of her home on Mead Street. She died instantly.

There was a deep irony to her death that stretched beyond the similarities to Hawkins. McCuller was the daughter of James McCuller, then executive-director of Action for a Better Community, and a member of the Crimi Committee.

Her death in 1983 became the first to be evaluated by the Complaint Investigation Committee borne of the committee. When her killer was cleared of wrongdoing, her father publicly denounced the review process he had helped create as a sham.

“When the last ounce of breath left my daughter’s body, the Crimi Committee report was dead, D-E-A-D dead,” McCuller told the Democrat and Chronicle in 1984. “You don’t go up to tombstones and start asking questions.”

Spurred in part by McCuller’s death and other high-profile police shootings of Black New Yorkers, then Gov. Mario Cuomo assembled a commission to evaluate racial bias in policing.

In 1987, the commission concluded there was no evidence of racial prejudice in police shootings, and that Black leaders were “acting on emotion rather than fact” when calling out systemic racism in policing.

″Exaggerated and emotional claims of police brutality by some minority representatives erodes their credibility and undermines their suggestions to ameliorate relationships,″ the commission report read.

Studies since have widely countered that conclusion.

Data from Mapping Police Violence, a nonprofit that tracks killings by police, shows that, between 2013 and 2019, police in New York killed 71 Black people and 53 white people. Adjusted for population, Black people were more than five times more likely to be killed by police than whites.

Prompted by mass demonstrations and looting in cities across New York in response to the death of George Floyd at the hands of police in Minneapolis, Gov. Andrew Cuomo followed in his father’s footsteps in June and signed an executive order mandating local police agencies to come up with a plan to “reinvent and modernize” police strategies based on community input by April 2021, or risk losing state funding.

The RASE Commission was formed in part to help with that task.

For many activists hungry for systemic change, phrases like “reinventing and modernizing” police are platitudes. They instead want to “defund” police departments, that is strip them of their budgets altogether, and reinvest the monies into impoverished neighborhoods.

Danielle Ponder, a Monroe County public defender who is perhaps best known as a musician whose crooning protest anthems have become a staple of Black Lives Matter rallies, is a proponent of the “defund” movement.

“What I think I’m realizing is the police were a system created in a flawed way, it was created in a racist manner,” Ponder said. “That system has to be eradicated. We essentially have a system that takes young white men, mostly from the suburbs who don’t have much experience with people of color, we give them guns, and tell them go police Black neighborhoods.”

Ponder believes policing in Rochester today too often targets petty crime in underserved, particularly Black, communities, and points to arrest statistics to bolster her view.

Of the 12,589 arrests Rochester police made last year, 8,355 were for misdemeanors. Roughly one in four arrests were for property crimes, according to the state Division of Criminal Justice Services. Countywide, nearly half of all the people arrested were Black, despite Black residents accounting for just 16 percent of the population.

“When all you have is a hammer, every problem becomes a nail,” Ponder said. “When all you have is the police, every problem becomes a crime.”

Following the death of Floyd, the Minneapolis City Council voted unanimously to dismantle their police department and create a new public safety model. While it remains uncertain what form that new model may take, the move fueled the national dialogue about defunding.

Activists in Rochester petitioned the City Council to cut the police budget in half. Lawmakers settled on decreasing spending on police by 5 percent and diverting the projected savings of $750,000 into a task force on police reform that ultimately became the RASE Commission.

“Folks were excited when they heard what was happening in Minneapolis, but did you read the fine print,” said City Council member Jackie Ortiz. “When? How? That still has to be thought through, you’re not going to say, ‘Sorry, nobody come to work.’”

MAYBE THE RIGHT TIME IS NOW

As the history of police reform in Rochester shows, substantive change can be a long and arduous process. But months of nationwide civil unrest has many stakeholders believing this time will be different.

“I’ve been a cop here for 35 years, I’ve never seen the chief and sheriff get together on a Friday night and say, ‘What happened in Minneapolis, we need to call it as it is, we got to make a statement,’” Baxter said. “I think we have an opportunity now that we didn’t have before.”

Willie Lightfoot, a Rochester City Council member and liaison to the RASE Commission, said he believes the time is ripe for a sea change in local policing in the next year or two.

“This is going to drive not just the government, but it will drive unions, it will drive police officers and their conduct” Lightfoot said. “Everything is being viewed by the community, and the community is at the point where they have a no tolerance attitude, as they should.”

Even representatives of police unions, which have traditionally been resistant to reform, have expressed some openness to change.

Michael Mazzeo, president of the Rochester Police Locust Club, the police union, has publicly acknowledged that “there is some level of systemic racism” in the RPD and that something has to give.

At the same time, his union has chipped away at the powers of the Police Accountability Board, and he has said he does not see progress stemming from any task force or commission.

“You see these police chiefs that look like a police chief, they talk more like police information officers, because I don’t see any action, I don’t see any leadership,” Mazzeo said, at a news conference in July, following the city’s announcement that all police disciplinary files will be put online. “I don’t see any new initiatives that will bring us to a better place. They talk about transparency until you’re nauseous over it, yet I don’t see any transparency.”

Still, those remarks are a far cry from the antagonistic rhetoric of his predecessor, Ronald Evangelista, when it came to police reform. In a 2005 op-ed in the Democrat and Chronicle, Evangelista called Johnson’s Pathways program “hypocrisy at its finest” and denounced recommendations like placing cameras in police cars.

Asked during a wide-ranging interview with the Democrat and Chronicle in 1984 about tensions between police and communities of color, Evangelista grew indignant.

“You haven’t figured it out yet? You haven’t figured out why? The answer to the question, and no one ever wants to say it, is because Black people are responsible for most of the street crime in this country,” Evangelista said. “And by having a Black leader getting up and supporting Black people, he’s supporting his type of people. That’s very popular. Minorities, not just Blacks, are not popular with police, who are mostly white, middle-classed people.”

“Is there any way to change that?” the interviewer asked.

Evangelista responded: “Go tell the Black leaders to promote education instead of police mistrust.”

But killings and beatings of unarmed people of color by white Rochester police in the years since have perpetuated the mistrust.

There was Calvin Green, who was 30 when he was fatally shot five times at close range by Officer Gary Smith in 1988 while cowering in a crawlspace in his East Main Street apartment.

Rickey Bryant was 17 when police knocked him off his bicycle on Remington Street, pepper sprayed him, and beat him in a case of mistaken identity in 2016. The city paid $360,000 to settle a lawsuit brought by his family.

Two years later, in 2018, Christopher Pate was beaten and tased by police while walking on Bloss Street in another case of mistaken identity. One of the officers, Michael Sippel, was later convicted of assault.

This week, Rochester learned of the death of Prude on March 23. He was naked and unarmed when police confronted him on Jefferson Avenue and had been released from Strong Memorial Hospital only hours earlier after a mental health evaluation.

Of course, people of color do turn to police for help all the time. Calls for help from Black people were what prompted police to respond in Prude's case, and in the shooting deaths of Green, and before him, McCuller, and before her, Hawkins.

“I placed the phone call for my brother to get help, not for my brother to get lynched,” Prude's brother, Joe Prude, who called 911 to report that Daniel Prude was in distress, told reporters this week.

In the case of Hawkins, she and her husband were fighting in an apartment rented by her sister, Miranda Roach, who later testified before a grand jury that she called 911 after watching the violence against her sister escalate.

Where it all went down is now an empty lot that stands as a silent memorial to Rochester’s first true swing at a change to policing.

Gino Fanelli is a CITY staff writer. He can be reached at (585) 775-9692 or gino @rochester-citynews.com.

There, in a basement unit of what was then the Apollo Apartments, a teenage mother argued with her husband, who was said to have had a thing for pushing her around. That night, 18-year-old Denise Hawkins would be pushed so far she would wind up dead.

The argument got physical, as it often did, and the couple tussled into the kitchen, where Hawkins brandished a knife and slashed her husband’s cheek. Minutes later, there was a pounding at the front door.

“Police!” an officer yelled from the other side, the door reportedly bowing outward from the battering inside.

“Look out, she’s coming out with a knife!” the husband shouted.

Hawkins, still gripping the knife tightly in her hand, spilled into the exterior hallway, where two officers awaited with guns drawn. “Drop it!” the officers shouted in unison.

She took two more steps before one of the officers, Michael Leach, a 22-year-old rookie, put a bullet in her chest, killing her instantly.

The circumstances of her death and its aftermath are familiar: Hawkins was Black, Leach was white and on duty, and the Black community erupted at the idea of another white cop being too quick to the pull the trigger on a person of color.

Leach would be exonerated by a grand jury and go on to retire from the Rochester Police Department as a captain nearly 30 years later. He would, however, wind up doing a stretch in jail at one point in retirement for fatally shooting his own son in the motel room they shared after mistaking him for an intruder.

Outrage over Hawkins’ death and what was regarded by many to be a sham of an investigation into Leach moved City Council to appoint a blue-ribbon panel to examine how policing in Rochester could improve. The Citizens Committee on Police Affairs, dubbed the Crimi Committee after its chairman and local lawyer Charles Crimi, would recommend sweeping changes to the Rochester Police Department.

Most of the changes would ostensibly be adopted, at least on paper.

Yet now, a new task force is asking the same questions about policing that were raised and supposedly addressed by the Crimi Committee nearly a half-century ago, including matters of domestic disputes, recruitment, neighborhood relations, psychological testing of officers, and firearms training.

Those questions became all the more relevant this week with news that 41-year-old Daniel Prude died of asphyxiation after being restrained by Rochester police officers in March.

Evolutions in policing and the city offer the task force new ground to mine. But the similarities between Hawkins’ death and those of so many people of color at the hands of police in Rochester and elsewhere around the country in the decades since, have task force members revisiting old ground for whether the Crimi Commission recommendations worked or, worse, whether they were implemented at all.

“That’s the right question,” said Bill Johnson, the former mayor of Rochester and a co-chair of the new Racial and Structural Equity (RASE) Commission.

“There’s a lot of stuff that’s happened in the community, and what’s important is for us to not only know what happened, but what didn’t,” Johnson said. “Did any change materialize as a result of all of this work? Did these recommendations get phased out, or upgraded?”

NINETY-SEVEN RECOMMENDATIONS

The RASE Commission, a joint initiative of the administrations of Rochester Mayor Lovely Warren and Monroe County Executive Adam Bello, is less a police reform task force than it is an ambitiously broad effort to identify and address the roots of structural racism.

The commission, a panel of 21 people led by Johnson along with Muhammad Shafiq, a religious studies professor at Nazareth College, and Arline Santiago, a senior vice president at ESL Federal Credit Union, is expected to publish a report on its findings early next year. The report is supposed to touch on topics as varied as education, equitable housing, business development, and policing.

On the latter, Johnson has been there before; he served on the Crimi Committee and led his own program as mayor in 2004 called Pathways to Better Police-Community Relations.

“There were real changes in reporting and policy that came as the result of that (Crimi Committee) document, and that’s over 40 years old,” Johnson said in a phone interview. “That’s my benchmark.”

The Crimi Committee made 97 recommendations, 85 of which were approved by the City Council in 1977. A descendant of those recommendations is the fledgling Police Accountability Board, which evolved from a recommendation that internal police investigations into alleged officer misconduct include examination by a civilian review panel. The so-called Complaint Investigation Committee, for the first time, added a lone civilian to the misconduct review process.

But many of the Crimi Committee’s recommendations appear to have gone nowhere.

For instance, the committee called for officers to be better educated, citing a 1973 National Advisory Commission recommendation that all police officers by 1978 should have three years of college education.

The RPD currently requires its officers to have a high school diploma or equivalent.

The committee also noted that recruiting minority candidates would go a long way toward building credibility in city neighborhoods, and recommended “seriously considering” requiring officers to live in the city as a condition of their employment.

The city charter requires employees in the uppermost tiers of city government to live in Rochester, but carves out an exception for first responders. The state Public Officers Law exempts police officers and firefighters from municipal residency requirements. The most the city can require is that officers live in Monroe County or one of its five adjacent counties.

By the time Johnson launched his Pathways program, 28.5 percent of the RPD force was minority. Today, just 13 percent of Rochester police officers are non-white, and less than 15 percent live in the city, according to the RPD’s official roster.

Then there’s the Family Crisis Intervention (FACIT) program. FACIT is a mobile team made up of social work professionals designated to respond to domestic violence, attempted suicides, family crises, mental health calls, rapes, child abuse, and other issues where a social element is at play.

The Crimi Committee recommended that FACIT receive more support, and specifically called on the City Council to take steps to fully fund the program and expand it, if necessary.

When that recommendation was made in 1977, FACIT had eight social workers. Today, the team has 10 and was estimated to have taken 3,500 calls last year, when domestic violence complaints alone accounted for nearly 30,000 of the RPD’s calls for service.

MENTAL HEALTH A PRIORITY

There is little agreement between police and reform advocates about what change could and should look like. Where there is common ground, however, is in the belief that police should not be the first resort for mental health crises.

“There’s certain things we don’t want police officers learning as they go,” said Rochester Police Chief La’Ron Singletary. “There’s no amount of training I can offer, outside of policing, that is going to equate to what a social worker has or what a family therapist or mental health therapist has.”

One model for handling mental health calls that has caught the attention of some city officials and reform advocates is something called CAHOOTS, a nonprofit mobile crisis intervention program out of Eugene, Oregon. Instead of police being deployed to calls for service for mental health crises such as welfare checks, disorientation, and non-violent disputes, the program mobilizes two-person teams of a medic and a social worker.

“The last few incidents that involved someone in crisis, from viewing body camera footage, have been escalated primarily by the officers showing up on the scene,” said City Council member Mary Lupien. “They end up hurting the person by their escalation and lack of awareness of mental health issues.”

This is not a new revelation. The Crimi Committee highlighted family crises as among those situations that have the most potential to spiral out of control and become dangerous. Likewise, a report from the non-profit Treatment Advocacy Center said people with untreated mental illness are 16 times more likely to be killed by police than people without mental illness.

Monroe County Sheriff Todd Baxter lamented that police so often get dispatched to such situations and blamed what he called a societal “addiction to 911.”

“We’re the quickest form of government, and we’ve been asked to solve a lot of the world’s problems with a 911 phone call,” Baxter said. “Which, in some of those situations, a police officer, or a police department, is not designed to solve those problems.”

The Crimi Committee touched on that decades ago, pointing out that, at the time, just 10 percent of police activities were related to enforcing the law. The remainder of their time was spent responding to service calls.

IF ALL YOU HAVE IS A HAMMER . . .

Nearly eight years to the day after Hawkins was shot and killed, another young Black mother was fatally shot by Rochester police.

Alecia McCuller was just 21 years old when she was shot twice in the chest by Officer Thomas Whitmore. McCuller was allegedly wielding a knife and attempting to stab her boyfriend outside of her home on Mead Street. She died instantly.

There was a deep irony to her death that stretched beyond the similarities to Hawkins. McCuller was the daughter of James McCuller, then executive-director of Action for a Better Community, and a member of the Crimi Committee.

Her death in 1983 became the first to be evaluated by the Complaint Investigation Committee borne of the committee. When her killer was cleared of wrongdoing, her father publicly denounced the review process he had helped create as a sham.

“When the last ounce of breath left my daughter’s body, the Crimi Committee report was dead, D-E-A-D dead,” McCuller told the Democrat and Chronicle in 1984. “You don’t go up to tombstones and start asking questions.”

Spurred in part by McCuller’s death and other high-profile police shootings of Black New Yorkers, then Gov. Mario Cuomo assembled a commission to evaluate racial bias in policing.

In 1987, the commission concluded there was no evidence of racial prejudice in police shootings, and that Black leaders were “acting on emotion rather than fact” when calling out systemic racism in policing.

″Exaggerated and emotional claims of police brutality by some minority representatives erodes their credibility and undermines their suggestions to ameliorate relationships,″ the commission report read.

Studies since have widely countered that conclusion.

Data from Mapping Police Violence, a nonprofit that tracks killings by police, shows that, between 2013 and 2019, police in New York killed 71 Black people and 53 white people. Adjusted for population, Black people were more than five times more likely to be killed by police than whites.

Prompted by mass demonstrations and looting in cities across New York in response to the death of George Floyd at the hands of police in Minneapolis, Gov. Andrew Cuomo followed in his father’s footsteps in June and signed an executive order mandating local police agencies to come up with a plan to “reinvent and modernize” police strategies based on community input by April 2021, or risk losing state funding.

The RASE Commission was formed in part to help with that task.

For many activists hungry for systemic change, phrases like “reinventing and modernizing” police are platitudes. They instead want to “defund” police departments, that is strip them of their budgets altogether, and reinvest the monies into impoverished neighborhoods.

Danielle Ponder, a Monroe County public defender who is perhaps best known as a musician whose crooning protest anthems have become a staple of Black Lives Matter rallies, is a proponent of the “defund” movement.

“What I think I’m realizing is the police were a system created in a flawed way, it was created in a racist manner,” Ponder said. “That system has to be eradicated. We essentially have a system that takes young white men, mostly from the suburbs who don’t have much experience with people of color, we give them guns, and tell them go police Black neighborhoods.”

Ponder believes policing in Rochester today too often targets petty crime in underserved, particularly Black, communities, and points to arrest statistics to bolster her view.

Of the 12,589 arrests Rochester police made last year, 8,355 were for misdemeanors. Roughly one in four arrests were for property crimes, according to the state Division of Criminal Justice Services. Countywide, nearly half of all the people arrested were Black, despite Black residents accounting for just 16 percent of the population.

“When all you have is a hammer, every problem becomes a nail,” Ponder said. “When all you have is the police, every problem becomes a crime.”

Following the death of Floyd, the Minneapolis City Council voted unanimously to dismantle their police department and create a new public safety model. While it remains uncertain what form that new model may take, the move fueled the national dialogue about defunding.

Activists in Rochester petitioned the City Council to cut the police budget in half. Lawmakers settled on decreasing spending on police by 5 percent and diverting the projected savings of $750,000 into a task force on police reform that ultimately became the RASE Commission.

“Folks were excited when they heard what was happening in Minneapolis, but did you read the fine print,” said City Council member Jackie Ortiz. “When? How? That still has to be thought through, you’re not going to say, ‘Sorry, nobody come to work.’”

MAYBE THE RIGHT TIME IS NOW

As the history of police reform in Rochester shows, substantive change can be a long and arduous process. But months of nationwide civil unrest has many stakeholders believing this time will be different.

“I’ve been a cop here for 35 years, I’ve never seen the chief and sheriff get together on a Friday night and say, ‘What happened in Minneapolis, we need to call it as it is, we got to make a statement,’” Baxter said. “I think we have an opportunity now that we didn’t have before.”

Willie Lightfoot, a Rochester City Council member and liaison to the RASE Commission, said he believes the time is ripe for a sea change in local policing in the next year or two.

“This is going to drive not just the government, but it will drive unions, it will drive police officers and their conduct” Lightfoot said. “Everything is being viewed by the community, and the community is at the point where they have a no tolerance attitude, as they should.”

Even representatives of police unions, which have traditionally been resistant to reform, have expressed some openness to change.

Michael Mazzeo, president of the Rochester Police Locust Club, the police union, has publicly acknowledged that “there is some level of systemic racism” in the RPD and that something has to give.

At the same time, his union has chipped away at the powers of the Police Accountability Board, and he has said he does not see progress stemming from any task force or commission.

“You see these police chiefs that look like a police chief, they talk more like police information officers, because I don’t see any action, I don’t see any leadership,” Mazzeo said, at a news conference in July, following the city’s announcement that all police disciplinary files will be put online. “I don’t see any new initiatives that will bring us to a better place. They talk about transparency until you’re nauseous over it, yet I don’t see any transparency.”

Still, those remarks are a far cry from the antagonistic rhetoric of his predecessor, Ronald Evangelista, when it came to police reform. In a 2005 op-ed in the Democrat and Chronicle, Evangelista called Johnson’s Pathways program “hypocrisy at its finest” and denounced recommendations like placing cameras in police cars.

Asked during a wide-ranging interview with the Democrat and Chronicle in 1984 about tensions between police and communities of color, Evangelista grew indignant.

“You haven’t figured it out yet? You haven’t figured out why? The answer to the question, and no one ever wants to say it, is because Black people are responsible for most of the street crime in this country,” Evangelista said. “And by having a Black leader getting up and supporting Black people, he’s supporting his type of people. That’s very popular. Minorities, not just Blacks, are not popular with police, who are mostly white, middle-classed people.”

“Is there any way to change that?” the interviewer asked.

Evangelista responded: “Go tell the Black leaders to promote education instead of police mistrust.”

But killings and beatings of unarmed people of color by white Rochester police in the years since have perpetuated the mistrust.

There was Calvin Green, who was 30 when he was fatally shot five times at close range by Officer Gary Smith in 1988 while cowering in a crawlspace in his East Main Street apartment.

Rickey Bryant was 17 when police knocked him off his bicycle on Remington Street, pepper sprayed him, and beat him in a case of mistaken identity in 2016. The city paid $360,000 to settle a lawsuit brought by his family.

Two years later, in 2018, Christopher Pate was beaten and tased by police while walking on Bloss Street in another case of mistaken identity. One of the officers, Michael Sippel, was later convicted of assault.

This week, Rochester learned of the death of Prude on March 23. He was naked and unarmed when police confronted him on Jefferson Avenue and had been released from Strong Memorial Hospital only hours earlier after a mental health evaluation.

Of course, people of color do turn to police for help all the time. Calls for help from Black people were what prompted police to respond in Prude's case, and in the shooting deaths of Green, and before him, McCuller, and before her, Hawkins.

“I placed the phone call for my brother to get help, not for my brother to get lynched,” Prude's brother, Joe Prude, who called 911 to report that Daniel Prude was in distress, told reporters this week.

In the case of Hawkins, she and her husband were fighting in an apartment rented by her sister, Miranda Roach, who later testified before a grand jury that she called 911 after watching the violence against her sister escalate.

Where it all went down is now an empty lot that stands as a silent memorial to Rochester’s first true swing at a change to policing.

Gino Fanelli is a CITY staff writer. He can be reached at (585) 775-9692 or gino @rochester-citynews.com.

Speaking of...

Latest in News

More by Gino Fanelli

-

These small cannabis farmers say New York's legal weed rollout is ruining their lives

Mar 21, 2024 -

Man shakes fist at sun

Mar 15, 2024 -

Finger Lakes in a can, by way of Hollywood

Feb 13, 2024 - More »