If Rochester is a 'City of the Arts,' why don't we fund the arts?

By David Andreatta @david_andreatta and Rebecca Rafferty @rsrafferty

[

{

"name": "500x250 Ad",

"insertPoint": "5",

"component": "15667920",

"parentWrapperClass": "",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

CORRECTION 1.7.21: This article has been updated from its original version to reflect that Rochester has an ordinance that established a "percent for art" program. That program, however, has been dormant since its adoption in 2007. CITY had initially reported that no such ordinance was on the books.

Every year for as long as anyone can remember, and for as long as available records show, Monroe County adopts a budget that offers crumbs in the way of funding to arts and cultural organizations.

It happened again in December, when legislators approved a $1.2 billion spending plan for 2021 that set aside about one-tenth of a percent — roughly $1.4 million — for the arts.

To put that in perspective, consider that county spending on the arts topped $3 million more than 30 years ago, and that nearby Erie County is set to spend more than double that on arts and culture this year.

Although dozens of organizations make up Rochester’s arts and cultural scene, Monroe County legislators did what they have done for decades and allocated most of the largesse to a handful of stalwart groups.

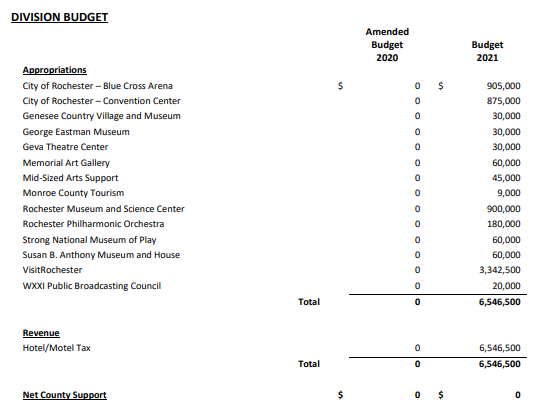

The bulk — $900,000 — went to the Rochester Museum and Science Center, which has a longstanding agreement with the county to share expenses. Another $180,000 went to the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra.

Most of the rest was split unevenly between seven other large institutions, like the Memorial Art Gallery and The Strong National Museum of Play, while a remaining $45,000 was sprinkled among 11 smaller arts organizations.

This is what passes for arts funding from Monroe County year after year.

RELATED: When it comes to public arts funding, RMSC is the elephant in the room

Amid a pandemic that has decimated the arts and a nationwide racial justice reckoning, large and small arts groups say the age-old funding formula has reached an inflection point on two fronts: the stagnant size of the county-funding pie and its inequitable distribution.

The formula is all too familiar to the dozens of small-fry arts groups that either get nothing from the pie or scrounge for leftovers after the cultural giants have been served their share.

“When I looked through the budget, I didn’t see anything different,” said Reenah Golden, founder of The Avenue BlackBox Theatre, a small performing arts company in northeast Rochester that was left out of the county budget. “The usual suspects are listed as approved or authorized agents, and there’s millions of dollars going into those organizations.”

What has evolved, the small groups say, is a two-tiered system of haves and have-nots. It is an art world version of class warfare that pits august institutions with well-heeled patrons against less-glamorous groups that lack political clout but serve more racially and economically diverse audiences.

Now those small groups are facing an existential crisis. Many are struggling and, in some cases, teetering on the brink of insolvency.

At the same time, major arts institutions have experienced stunning financial losses as a result of the pandemic, accompanied in some cases by furloughs and layoffs. A concern among them is that reallocating funding would siphon off monies on which they have come to depend and that are now shoring up their depleted balance sheets.

Advocates for the arts say the answer isn’t robbing Peter to pay Paul, but rather devising a more reliable and equitable public funding stream that is resilient to the vagaries of budget negotiations, where the arts is often an easy target.

“Not only do they need to reevaluate it, they need to be proactive and put in place steps so that we have clear and concise guidelines that the arts have funding, that the process is open and transparent to all organizations,” said Dawn Lipson, a longtime patron of the arts who heads the moribund Arts and Cultural Council of Greater Rochester. “You can’t call Rochester ‘The City of the Arts’ and not support the arts,” she said. “That’s what’s going on.”

A VIBRANT ARTS COMMUNITY

To say that Rochester has among the most robust and outsized arts and cultural scenes in the country isn’t puffery.

The city has made the National Center for Arts Research annual list of “The Top 40 Most Vibrant Arts Communities” three out of the last six years. Its most recent appearance was in 2018, when it ranked at No. 17 between Chicago and Austin.

The center calculates that arts and culture pump $93 million into the Monroe County economy annually, fueled by more than 1,500 full-time employees, 2,100 part-timers, and some 6,600 volunteers in the sector.

The Center for Governmental Research, a consulting outfit in Rochester, drew similar conclusions about the impact of the arts here in a 2019 study commissioned by legacy cultural groups.

But CGR researchers also identified shortcomings, particularly a lack of public funding and cohesion within the arts community.

“While strong support for the sector exists informally within the community, formal and structured support from the public sector is lacking,” the study read. “Nor does Rochester’s cultural sector have an organized long range planning process.”

BELLO COURTS THE ARTS

It was against that backdrop that Monroe County Executive Adam Bello, who took office a year ago, set about courting the arts community during his campaign in 2019.

He met with the heads of big institutions and bit players, often tempering a sheepish acknowledgment that the arts were not his bailiwick with a promise to listen, and seizing an opportunity to preach to the choir.

“A city our size, our investments in art are well below the per capita numbers of our peer counties,” Bello told an audience of artists at the Rochester Contemporary Art Center in October 2019 to applause.

“Right now,” Bello went on, “the decisions about how we as a county are investing in the arts community happen behind closed doors and are announced when a budget is proposed.” There was more applause.

Yet a year later, Bello proposed his own budget that mimicked the archaic arts funding pattern that he eschewed on the campaign trail.

To what extent peer counties and cities fund their local arts groups is difficult to pinpoint. No national or state arts advocacy organizations aggregate such figures.

The best way to tally them is by poring over municipal budgets, a laborious endeavor that risks arriving at incomplete totals because many budgets don’t detail small line item allocations.

Even with those pitfalls in mind, though, the budgets of Erie and Onondaga counties, which encompass the cities of Buffalo and Syracuse, unequivocally show a greater and more diverse investment in the arts than in Monroe.

Erie County adopted a budget that included $6.6 million for 88 arts and cultural organizations, from giants like the Albright-Knox Art Gallery to the mid-sized Buffalo Inner City Ballet and the tiny Cheektowaga Community Chorus.

Onondaga County is about two-thirds the size of Monroe in terms of population, but it set aside $1.3 million for 46 arts and cultural groups, including 32 that received grants of $10,000 or less. The county distributes those small grants through a nonprofit, CNY Arts, that it entrusts to identify deserving arts groups and individual artists.

By contrast, Monroe County gives more than three-quarters of its $1.4 million in arts funding to two organizations and a fifth of it to another seven. (One of those seven is CITY’s parent, WXXI Public Broadcasting, which receives $20,000 annually.)

Barely 3 percent of the funding — $45,000 — is reserved for “mid-sized arts groups,” which the county defines as those with budgets of between $100,000 and $1.5 million. In recent years, the same 11 groups have split that share in grants of between $2,500 and $5,500.

The CGR study identified 64 arts and cultural organizations in Monroe County, although advocates for the arts estimated the number to be far higher.

“What we see in other progressive cities, the curve is completely flipped,” said Bleu Cease, the executive director of the Rochester Contemporary Art Center, who has been a vocal advocate for re-evaluating how county arts funding is administered and establishing a unified coalition to lobby for the arts in local government.

“It’s not 90 percent to one big organization,” he said. “It’s 50 percent to a bunch of small organizations. Other cities are rebalancing their really old models because small groups need that support.”

The 11 “mid-sized arts groups” that got money from Monroe County are not listed in the budget, but they included outfits like Blackfriars Theatre, Deep Arts, Garth Fagan Dance, and Rochester City Ballet.

Unlike in other municipalities that rely on an arts liaison to funnel small grants to deserving groups, Monroe County leaves its “mid-sized arts groups” support to the discretion of its budget director.

Under questioning by legislators last month, the budget director, Robert Franklin, explained how he determines who gets what.

“I have about seven factors that I look at,” he said, citing tax records and earned revenues as examples. “Then I basically rate them on a scale of, like, they get one point for each criteria they meet and, I think there are eight criteria.”

Franklin noted the recipients hardly change from year to year and said that his office fields few inquiries from arts groups about obtaining help. Representatives of arts groups have complained for years that they don’t know where in county government to turn for help.

The county declined to respond to several requests for specifics about the selection process and what groups were chosen.

CITY independently obtained lists from prior years, however. Notably, those lists showed that the county has stopped short of allocating the entire $45,000 that was budgeted. Last year, it gave out $41,000. In 2018, it gave out just $37,500.

NO COMMISSION, NO COUNCIL, NO VOICE

Nearly every American city and county the size of Rochester and Monroe County has some sort of arts commission that advises local government on cultural matters or a nonprofit that is the primary voice for arts groups and artists, like CNY Arts. Many places have both.

Rochester and Monroe County have neither. Indeed, neither the City Council nor the County Legislature has an arts and cultural committee.

For years, the Arts and Cultural Council of Greater Rochester, a nonprofit organization whose function was to help direct state arts grants and administer a group health insurance plan for artists, was a voice for the community.

But the council has barely been functional since financial pressures forced it to vacate its offices on Goodman Street in 2014, and it is now in the process of dissolving.

“We call ourselves a city of the arts, we use that as a kind of promotional thing,” said Thomas Warfield, a singer and theater and dance professor at the Rochester Institute of Technology. “For a city our size, with so many artists, to not have something like a commission or a council, it just boggles the mind.”

Once upon a time, there was something called the Metropolitan Arts Resources Committee. Created by the county in 1967 to help prioritize public subsidies for the arts, it was funded with $15,000.

Lucien Morin, a former county executive who was a county legislator when the committee was established, called the investment at the time, “the first step toward opening the coffers for large-scale public support of the arts.”

Nine years later, in the midst of a nationwide fiscal crisis, the committee was fighting for survival.

James Breese, the late Henrietta supervisor and a Republican county legislator during the crisis, captured the zeitgeist in the cash-strapped county government when he proposed during budget negotiations in 1976 to “take a real meat ax” to arts and cultural groups.

“These people think they have a divine right to government money,” Breese said. “The more government gives, the less these institutions will try to support themselves.”

The Metropolitan Arts Resources Committee was dissolved five years later, and the amount of funding the county offered to arts and cultural groups climbed at a much slower clip.

Funding reached its zenith at $3.1 million in 1989 under the first and, until that time, only Democratic administration in that of County Executive Thomas Frey.

Republicans took control of the County Legislature the next year, and the executive branch soon after. When it came to funding for the arts, austerity would be the mantra moving forward and the amount allocated to culture was gradually whittled down to its current $1.4 million.

Arts organizations had high hopes that would change when Bello was sworn in last year as the first Democratic executive in more than a generation. A month after he took office, he released a report by his transition team that made two recommendations when it came to the arts.

The first was to “establish a body which effectively and accurately represents the arts community in Monroe County to provide guidance on issues relating to arts and culture, public art, and arts funding.”

The other was to evaluate the county’s arts policies to ensure it represents the diversity of the arts community.

A month later, the pandemic struck and acting on the recommendations was put on hold.

CITY EYES A ‘PERCENT FOR ART’

Advocates for the arts have described engaging in what they believed were fruitful talks prior to the pandemic with current county and city officials about re-thinking government’s role in funding cultural groups.

Mayor Lovely Warren is said to be on the cusp of unveiling what is known as a “percent for art” program that would set aside a small percentage of the cost of public works projects for arts funding.

Her administration’s Rochester 2034 Plan, a blueprint for the future of the city, references a “percent for art” ordinance, which the city adopted in 2007. But that law appears to have been overlooked and is today virtually dormant.

Indeed, city officials who were interviewed for this story could not say how the ordinance has been applied since its adoption during the administration of Mayor Robert Duffy.

The law was to take effect in 2009 and was modeled after countless other "percent for art" ordinances around the country that set aside 1 percent of the total budget of a capital improvement project for public art.

But the law was amended just as it was to take place, and that legislation acknowledged that the city had no money to commit to public art in that year's capital improvement plan and that putting 1 percent aside for art was "a goal." There is nothing in City Council records since to suggest that goal was ever met.

Mayoral spokesperson Justin Roj confirmed that the mayor and her lieutenants were deep into a re-examination of the city’s arts funding, including a "percent for art" ordinance, but declined to provide details.

“Percent for art” programs have been around in the United States since Philadelphia adopted the first municipal ordinance in 1959. More than 100 city, county, and state governments have since launched such programs, according to the National Endowment for the Arts.

The programs generally set aside 1 percent of the total budget of a capital improvement project for public art. In most cases, a municipal arts council is responsible for administering the funds and the artwork.

The city does invest in arts programs and events, mostly through a $1 million budget for “special events” and its Department of Recreation and Human Services.

Not all of the special events budget goes to arts and culture, but it supports things like public Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra concerts, the Fringe Festival, and the Jazz Festival, which gets the largest share of the pie. Last year, the Jazz Festival was awarded $243,000.

The Department of Recreation and Human Services furnished a list of music, dance, and visual art programs that are not delineated in the budget but collectively received about $200,000.

WHY NOT A TAX FOR ART?

It might be tempting for politicians to think that proposing a tax for the arts in times like these would get them laughed out of office. But they might be surprised.

Voters in Jersey City, New Jersey, in November overwhelmingly supported a referendum that made the city the first municipality in the state to establish a tax to benefit the arts. The referendum is expected to be approved by the City Council.

The tax would charge residents 5 cents per $1,000 of assessed property value.

If the same formula were applied to Monroe County, where all taxable properties are collectively valued at $48.7 billion, such a tax would raise $2.4 million for the arts.

The plan in Jersey City borrows from those used in several municipalities across the country.

In three Michigan counties, residents pay a property tax that helps fund the Detroit Institute of Arts, which offers free admission to residents. In St. Louis, property taxes generate about $85 million for arts and cultural institutions.

Those examples were cited in a 2018 consultant’s study by AMS Planning & Research that Rochester commissioned that examined, among other things, new ways of funding the arts. Researchers also noted a rental car tax in Las Vegas and a tax on cigarette purchases in Cuyahoga County, which includes Cleveland.

Money allocated to the arts in Monroe County has for decades been derived from a hotel room occupancy tax that charges guests a 6 percent fee.

In recent years, the tax has generated close to $9 million annually. But most of that is spent unevenly on county parks, the convention center, BlueCross Arena, and the county’s tourism bureau, VisitRochester, whose $3.3 million slice is the biggest of the bunch.

Only a fraction of the money — $1.4 million — is set aside for arts and cultural institutions and almost all of it goes to nine organizations.

Even if the pie were larger, though, so many small-fry arts groups that have been shut out of accessing the funds for so long are skeptical that they will ever get a piece of the pie.

Even if the pie were larger, though, many small arts groups are skeptical they could ever get a piece. Years of either being rejected or unable to get answers as to how to apply has left them resigned to the idea that accessing funding is all about who you know.

Nydia Padilla-Rodriguez, the founder and artistic director at Borinquen Dance Theatre, a Latin dance company, said she stopped applying for funding from the county after being turned down time and again.

“I just think the process needs to change,” Padilla-Rodriguez said. “I believe it’s clearly political.”

David Andreatta is CITY's editor. Rebecca Rafferty is CITY's life editor. They can be reached at [email protected] and [email protected].

Every year for as long as anyone can remember, and for as long as available records show, Monroe County adopts a budget that offers crumbs in the way of funding to arts and cultural organizations.

It happened again in December, when legislators approved a $1.2 billion spending plan for 2021 that set aside about one-tenth of a percent — roughly $1.4 million — for the arts.

To put that in perspective, consider that county spending on the arts topped $3 million more than 30 years ago, and that nearby Erie County is set to spend more than double that on arts and culture this year.

Although dozens of organizations make up Rochester’s arts and cultural scene, Monroe County legislators did what they have done for decades and allocated most of the largesse to a handful of stalwart groups.

The bulk — $900,000 — went to the Rochester Museum and Science Center, which has a longstanding agreement with the county to share expenses. Another $180,000 went to the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra.

Most of the rest was split unevenly between seven other large institutions, like the Memorial Art Gallery and The Strong National Museum of Play, while a remaining $45,000 was sprinkled among 11 smaller arts organizations.

This is what passes for arts funding from Monroe County year after year.

RELATED: When it comes to public arts funding, RMSC is the elephant in the room

Amid a pandemic that has decimated the arts and a nationwide racial justice reckoning, large and small arts groups say the age-old funding formula has reached an inflection point on two fronts: the stagnant size of the county-funding pie and its inequitable distribution.

The formula is all too familiar to the dozens of small-fry arts groups that either get nothing from the pie or scrounge for leftovers after the cultural giants have been served their share.

“When I looked through the budget, I didn’t see anything different,” said Reenah Golden, founder of The Avenue BlackBox Theatre, a small performing arts company in northeast Rochester that was left out of the county budget. “The usual suspects are listed as approved or authorized agents, and there’s millions of dollars going into those organizations.”

What has evolved, the small groups say, is a two-tiered system of haves and have-nots. It is an art world version of class warfare that pits august institutions with well-heeled patrons against less-glamorous groups that lack political clout but serve more racially and economically diverse audiences.

Now those small groups are facing an existential crisis. Many are struggling and, in some cases, teetering on the brink of insolvency.

At the same time, major arts institutions have experienced stunning financial losses as a result of the pandemic, accompanied in some cases by furloughs and layoffs. A concern among them is that reallocating funding would siphon off monies on which they have come to depend and that are now shoring up their depleted balance sheets.

Advocates for the arts say the answer isn’t robbing Peter to pay Paul, but rather devising a more reliable and equitable public funding stream that is resilient to the vagaries of budget negotiations, where the arts is often an easy target.

“Not only do they need to reevaluate it, they need to be proactive and put in place steps so that we have clear and concise guidelines that the arts have funding, that the process is open and transparent to all organizations,” said Dawn Lipson, a longtime patron of the arts who heads the moribund Arts and Cultural Council of Greater Rochester. “You can’t call Rochester ‘The City of the Arts’ and not support the arts,” she said. “That’s what’s going on.”

A VIBRANT ARTS COMMUNITY

To say that Rochester has among the most robust and outsized arts and cultural scenes in the country isn’t puffery.

The city has made the National Center for Arts Research annual list of “The Top 40 Most Vibrant Arts Communities” three out of the last six years. Its most recent appearance was in 2018, when it ranked at No. 17 between Chicago and Austin.

The center calculates that arts and culture pump $93 million into the Monroe County economy annually, fueled by more than 1,500 full-time employees, 2,100 part-timers, and some 6,600 volunteers in the sector.

The Center for Governmental Research, a consulting outfit in Rochester, drew similar conclusions about the impact of the arts here in a 2019 study commissioned by legacy cultural groups.

But CGR researchers also identified shortcomings, particularly a lack of public funding and cohesion within the arts community.

“While strong support for the sector exists informally within the community, formal and structured support from the public sector is lacking,” the study read. “Nor does Rochester’s cultural sector have an organized long range planning process.”

BELLO COURTS THE ARTS

It was against that backdrop that Monroe County Executive Adam Bello, who took office a year ago, set about courting the arts community during his campaign in 2019.

He met with the heads of big institutions and bit players, often tempering a sheepish acknowledgment that the arts were not his bailiwick with a promise to listen, and seizing an opportunity to preach to the choir.

“A city our size, our investments in art are well below the per capita numbers of our peer counties,” Bello told an audience of artists at the Rochester Contemporary Art Center in October 2019 to applause.

“Right now,” Bello went on, “the decisions about how we as a county are investing in the arts community happen behind closed doors and are announced when a budget is proposed.” There was more applause.

Yet a year later, Bello proposed his own budget that mimicked the archaic arts funding pattern that he eschewed on the campaign trail.

To what extent peer counties and cities fund their local arts groups is difficult to pinpoint. No national or state arts advocacy organizations aggregate such figures.

The best way to tally them is by poring over municipal budgets, a laborious endeavor that risks arriving at incomplete totals because many budgets don’t detail small line item allocations.

Even with those pitfalls in mind, though, the budgets of Erie and Onondaga counties, which encompass the cities of Buffalo and Syracuse, unequivocally show a greater and more diverse investment in the arts than in Monroe.

Erie County adopted a budget that included $6.6 million for 88 arts and cultural organizations, from giants like the Albright-Knox Art Gallery to the mid-sized Buffalo Inner City Ballet and the tiny Cheektowaga Community Chorus.

Onondaga County is about two-thirds the size of Monroe in terms of population, but it set aside $1.3 million for 46 arts and cultural groups, including 32 that received grants of $10,000 or less. The county distributes those small grants through a nonprofit, CNY Arts, that it entrusts to identify deserving arts groups and individual artists.

By contrast, Monroe County gives more than three-quarters of its $1.4 million in arts funding to two organizations and a fifth of it to another seven. (One of those seven is CITY’s parent, WXXI Public Broadcasting, which receives $20,000 annually.)

Barely 3 percent of the funding — $45,000 — is reserved for “mid-sized arts groups,” which the county defines as those with budgets of between $100,000 and $1.5 million. In recent years, the same 11 groups have split that share in grants of between $2,500 and $5,500.

The CGR study identified 64 arts and cultural organizations in Monroe County, although advocates for the arts estimated the number to be far higher.

“What we see in other progressive cities, the curve is completely flipped,” said Bleu Cease, the executive director of the Rochester Contemporary Art Center, who has been a vocal advocate for re-evaluating how county arts funding is administered and establishing a unified coalition to lobby for the arts in local government.

“It’s not 90 percent to one big organization,” he said. “It’s 50 percent to a bunch of small organizations. Other cities are rebalancing their really old models because small groups need that support.”

The 11 “mid-sized arts groups” that got money from Monroe County are not listed in the budget, but they included outfits like Blackfriars Theatre, Deep Arts, Garth Fagan Dance, and Rochester City Ballet.

Unlike in other municipalities that rely on an arts liaison to funnel small grants to deserving groups, Monroe County leaves its “mid-sized arts groups” support to the discretion of its budget director.

Under questioning by legislators last month, the budget director, Robert Franklin, explained how he determines who gets what.

“I have about seven factors that I look at,” he said, citing tax records and earned revenues as examples. “Then I basically rate them on a scale of, like, they get one point for each criteria they meet and, I think there are eight criteria.”

Franklin noted the recipients hardly change from year to year and said that his office fields few inquiries from arts groups about obtaining help. Representatives of arts groups have complained for years that they don’t know where in county government to turn for help.

The county declined to respond to several requests for specifics about the selection process and what groups were chosen.

CITY independently obtained lists from prior years, however. Notably, those lists showed that the county has stopped short of allocating the entire $45,000 that was budgeted. Last year, it gave out $41,000. In 2018, it gave out just $37,500.

NO COMMISSION, NO COUNCIL, NO VOICE

Nearly every American city and county the size of Rochester and Monroe County has some sort of arts commission that advises local government on cultural matters or a nonprofit that is the primary voice for arts groups and artists, like CNY Arts. Many places have both.

Rochester and Monroe County have neither. Indeed, neither the City Council nor the County Legislature has an arts and cultural committee.

For years, the Arts and Cultural Council of Greater Rochester, a nonprofit organization whose function was to help direct state arts grants and administer a group health insurance plan for artists, was a voice for the community.

But the council has barely been functional since financial pressures forced it to vacate its offices on Goodman Street in 2014, and it is now in the process of dissolving.

“We call ourselves a city of the arts, we use that as a kind of promotional thing,” said Thomas Warfield, a singer and theater and dance professor at the Rochester Institute of Technology. “For a city our size, with so many artists, to not have something like a commission or a council, it just boggles the mind.”

Once upon a time, there was something called the Metropolitan Arts Resources Committee. Created by the county in 1967 to help prioritize public subsidies for the arts, it was funded with $15,000.

Lucien Morin, a former county executive who was a county legislator when the committee was established, called the investment at the time, “the first step toward opening the coffers for large-scale public support of the arts.”

Nine years later, in the midst of a nationwide fiscal crisis, the committee was fighting for survival.

James Breese, the late Henrietta supervisor and a Republican county legislator during the crisis, captured the zeitgeist in the cash-strapped county government when he proposed during budget negotiations in 1976 to “take a real meat ax” to arts and cultural groups.

“These people think they have a divine right to government money,” Breese said. “The more government gives, the less these institutions will try to support themselves.”

The Metropolitan Arts Resources Committee was dissolved five years later, and the amount of funding the county offered to arts and cultural groups climbed at a much slower clip.

Funding reached its zenith at $3.1 million in 1989 under the first and, until that time, only Democratic administration in that of County Executive Thomas Frey.

Republicans took control of the County Legislature the next year, and the executive branch soon after. When it came to funding for the arts, austerity would be the mantra moving forward and the amount allocated to culture was gradually whittled down to its current $1.4 million.

Arts organizations had high hopes that would change when Bello was sworn in last year as the first Democratic executive in more than a generation. A month after he took office, he released a report by his transition team that made two recommendations when it came to the arts.

The first was to “establish a body which effectively and accurately represents the arts community in Monroe County to provide guidance on issues relating to arts and culture, public art, and arts funding.”

The other was to evaluate the county’s arts policies to ensure it represents the diversity of the arts community.

A month later, the pandemic struck and acting on the recommendations was put on hold.

CITY EYES A ‘PERCENT FOR ART’

Advocates for the arts have described engaging in what they believed were fruitful talks prior to the pandemic with current county and city officials about re-thinking government’s role in funding cultural groups.

Mayor Lovely Warren is said to be on the cusp of unveiling what is known as a “percent for art” program that would set aside a small percentage of the cost of public works projects for arts funding.

Her administration’s Rochester 2034 Plan, a blueprint for the future of the city, references a “percent for art” ordinance, which the city adopted in 2007. But that law appears to have been overlooked and is today virtually dormant.

Indeed, city officials who were interviewed for this story could not say how the ordinance has been applied since its adoption during the administration of Mayor Robert Duffy.

The law was to take effect in 2009 and was modeled after countless other "percent for art" ordinances around the country that set aside 1 percent of the total budget of a capital improvement project for public art.

But the law was amended just as it was to take place, and that legislation acknowledged that the city had no money to commit to public art in that year's capital improvement plan and that putting 1 percent aside for art was "a goal." There is nothing in City Council records since to suggest that goal was ever met.

Mayoral spokesperson Justin Roj confirmed that the mayor and her lieutenants were deep into a re-examination of the city’s arts funding, including a "percent for art" ordinance, but declined to provide details.

“Percent for art” programs have been around in the United States since Philadelphia adopted the first municipal ordinance in 1959. More than 100 city, county, and state governments have since launched such programs, according to the National Endowment for the Arts.

The programs generally set aside 1 percent of the total budget of a capital improvement project for public art. In most cases, a municipal arts council is responsible for administering the funds and the artwork.

The city does invest in arts programs and events, mostly through a $1 million budget for “special events” and its Department of Recreation and Human Services.

Not all of the special events budget goes to arts and culture, but it supports things like public Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra concerts, the Fringe Festival, and the Jazz Festival, which gets the largest share of the pie. Last year, the Jazz Festival was awarded $243,000.

The Department of Recreation and Human Services furnished a list of music, dance, and visual art programs that are not delineated in the budget but collectively received about $200,000.

WHY NOT A TAX FOR ART?

It might be tempting for politicians to think that proposing a tax for the arts in times like these would get them laughed out of office. But they might be surprised.

Voters in Jersey City, New Jersey, in November overwhelmingly supported a referendum that made the city the first municipality in the state to establish a tax to benefit the arts. The referendum is expected to be approved by the City Council.

The tax would charge residents 5 cents per $1,000 of assessed property value.

If the same formula were applied to Monroe County, where all taxable properties are collectively valued at $48.7 billion, such a tax would raise $2.4 million for the arts.

The plan in Jersey City borrows from those used in several municipalities across the country.

In three Michigan counties, residents pay a property tax that helps fund the Detroit Institute of Arts, which offers free admission to residents. In St. Louis, property taxes generate about $85 million for arts and cultural institutions.

Those examples were cited in a 2018 consultant’s study by AMS Planning & Research that Rochester commissioned that examined, among other things, new ways of funding the arts. Researchers also noted a rental car tax in Las Vegas and a tax on cigarette purchases in Cuyahoga County, which includes Cleveland.

Money allocated to the arts in Monroe County has for decades been derived from a hotel room occupancy tax that charges guests a 6 percent fee.

In recent years, the tax has generated close to $9 million annually. But most of that is spent unevenly on county parks, the convention center, BlueCross Arena, and the county’s tourism bureau, VisitRochester, whose $3.3 million slice is the biggest of the bunch.

Only a fraction of the money — $1.4 million — is set aside for arts and cultural institutions and almost all of it goes to nine organizations.

Even if the pie were larger, though, so many small-fry arts groups that have been shut out of accessing the funds for so long are skeptical that they will ever get a piece of the pie.

Even if the pie were larger, though, many small arts groups are skeptical they could ever get a piece. Years of either being rejected or unable to get answers as to how to apply has left them resigned to the idea that accessing funding is all about who you know.

Nydia Padilla-Rodriguez, the founder and artistic director at Borinquen Dance Theatre, a Latin dance company, said she stopped applying for funding from the county after being turned down time and again.

“I just think the process needs to change,” Padilla-Rodriguez said. “I believe it’s clearly political.”

David Andreatta is CITY's editor. Rebecca Rafferty is CITY's life editor. They can be reached at [email protected] and [email protected].