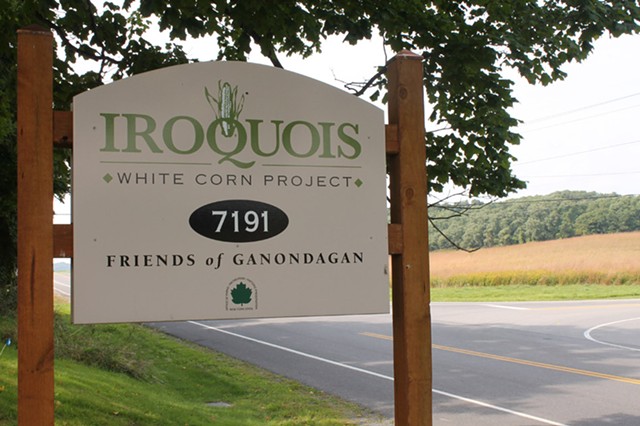

PHOTO COURTESY CAROL WHITE LLEWELLYN

The annual Iroquois White Corn Project includes a post-harvest husking bee, during which volunteers can assist with braiding corn leaves in preparation for hanging and drying.

[

{

"name": "500x250 Ad",

"insertPoint": "5",

"component": "15667920",

"parentWrapperClass": "",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

Imagine a plant with the power to fuel some of history's mightiest empires and simultaneously topple them with an epidemic. Imagine being able to harness the plant to ensure it helps humankind instead of hurts it, only to be foiled by corporations that repress the message.

What sounds like the makings of an incredible story is also the story of corn — white corn, to be precise — and it is the story that the Iroquois White Corn Project of the Ganondagan State Historic Site wants to tell.

Originally founded by scholar and activist Dr. John Mohawk in 1997, the project aims to change the way we think about corn, and was rebooted in 2012 as a means to grow, promote, and sell the same corn that sustained the Haudenosaunee people, also known as the Iroquois, for centuries.

"This is about food sovereignty, getting away from the fast food and the food deserts that surround us," explains G. Peter Jemison, the manager at Ganondagan.

White corn is a "flour" corn that differs from the familiar "sweet" corn (eaten on the cob or from a can), and "dent" corn, which gives us everything from fuel ethanol to high fructose corn syrup that has become a staple of the American diet and health concern. Studies have linked high fructose corn syrup to the rise of Type 2 diabetes and related conditions in people worldwide, including the Haudenosaunee.

"There's corn syrup in everything," Jemison says. "It's used as a sweetener, an extender,in beverages and other things. What we're working on is a 'slow food,' it's not absorbed like a quick hit of sugar. White corn is a slower food source. It takes a while for the body to absorb and use."

The beauty of the Iroquois White Corn Project is that its products — hulled corn and corn flour — serve two purposes: Providing nutrition to Indigenous communities that are so often food deserts and a source of jobs and revenue for Gandondagan through its sale to the general public.

The traditional method of cultivating and processing white corn is labor-intensive work. Jemison says a network of white corn producers is growing, with suppliers in the Tuscarora and Mohawk nations, and processors as far away as the Oneida Nation of Wisconsin.

"It's not a big money-maker but it offers an opportunity for youth to develop training and job skills," Jemison says. "We have young people that are actually carrying on the project, now that we're back again and we've got orders that we're trying to fill, but we're not trying to get too big. That's the challenge. But we also have to make ends meet — make enough to cover the expenses, and provide employment."

Not getting too big means demand often exceeds supply. To meet demand, the project is training other Haudenosaunee communities to build their own self-sufficient operations. A case in point is the Seneca Nation — one of six that formed the Iroquois Confederacy — which now cultivates its own white corn and many other vegetables.

The Haudenosaunee have been growing white corn in this region for at least 1,400 years. The corn was the dominant crop in 1687, when the Marquis de Denonville, on a rampage through Seneca Nation territory, destroyed Ganondagan and burned more than a million bushels of corn in the process, crippling the nation's economy.

Processing the corn starts with harvesting by hand. Then the corn is brought to Ganondagan around October for what is known as a "husking bee," in which the corn is stripped of its husk except for the three layers closest to the cob.

Most years, the Iroquois White Corn Project welcomes volunteers to help with husking. This year, the pandemic meant temporarily closing the doors. While events at Ganondagan are on hold, keep an eye on the website (ganondagan.org.) for updates as the statewide reopening process continues.

The shutdown did not affect corn growing operations at Ganondagan, however, as the field was scheduled to be left fallow this year to restore the soil's nutrients. Farms that supply the project have continued to grow white corn, though, and processing will resume after this fall's harvest.

The husking bee is followed by nixtamalization, the process of soaking and cooking the corn in lye and water. Nixtamalization is the key to unlocking the nutrients in the kernels. The process takes its name from the same Nahuatl (an ancient group of languages including Aztec) root word as the more familiar "tamales," and its history dates back to the birth of the Maya culture in Guatemala.

Guatemala and Ganondagan are more than 3,000 miles apart. So was the process shared through trade and cultural exchange, or did the Haudenosaunee develop the same solution independently?

"I think it probably developed independently," Jemison says. "We certainly developed the corn varieties that can survive in the shorter growing season of the northern latitudes." He pointed out that the hardwood used in traditional nixtamalization is plentiful in this area.

After nixtamalization, the corn is thoroughly washed and the remaining husk is scrubbed off. Hulled corn goes to consumer markets, and can be mixed into soup, chowder, chili, salads, stews, salsas, or anything into which you'd mix hominy or beans. Corn that was sorted out gets roasted and ground and processed into white corn flour.

Products from the Iroquois White Corn Project can be purchased at ganondagan.org/whitecorn/shop.

Most of the corn grown in the United States today is genetically modified. While GMO corn has not been proven to be any more harmful than non-GMO corn, the pesticides the crop is designed to resist can be toxic.

Protecting white corn heirloom seeds from agribusiness giants is part of the job at the Iroquois White Corn Project.

"It's a big issue, protecting our seeds," Jemison says. "It's about respecting the farmers we work with, and supporting the autonomous work that they do."

Declan Ryan is a freelance writer for CITY. Feedback on this story can be directed to Rebecca Rafferty, CITY's arts & entertainment editor, at [email protected].

In This Guide...

Speaking of...

-

Wampum exhibit at Ganondagan is a homecoming for history

May 6, 2023 -

Seneca artist G. Peter Jemison awarded national arts fellowship

Feb 13, 2023 -

Five spots for $10 lunches

Mar 31, 2022 - More »

Latest in Fall Guide

More by Declan Ryan

-

Quarantined: COVID-19 moves musicians to think outside the box

Mar 24, 2020 -

FAMILY | 2nd Sunday Storytime

Mar 4, 2020 -

FAMILY | Musical Mystery Tour

Mar 4, 2020 - More »